THE recent surge in interest in building new abattoirs around Australia stands in contrast to the challenges the red meat processing sector has faced in recent decades.

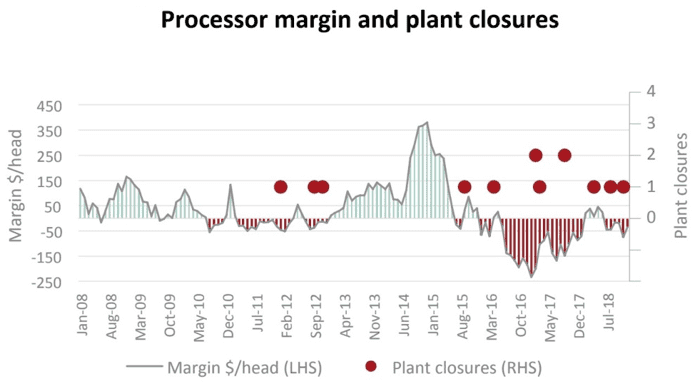

More than 90 abattoirs closed across Australia between the mid 1980s and 2000s, according to statistics reported in the ACCC’s 2017 cattle and beef market study, while a further 16 cattle and sheep plants have closed in the past decade, according to a March 2019 AMPC report.

Gradual declines in sheep and cattle populations over that period and rising labour, energy and regulatory costs have been among the major catalysts for the ongoing rationalisation in the sector.

The trend has led to fewer numbers of larger processors operating around the country, as existing operators have sought to drive efficiency through scale.

The ACCC report also noted that despite the  loss of many individual processing facilities, overall processing capacity has increased over time, as bigger abattoirs have grown larger.

loss of many individual processing facilities, overall processing capacity has increased over time, as bigger abattoirs have grown larger.

The backdrop of challenging conditions and multiple abattoir closures in recent decades begs the question: why the sudden recent interest in building new ones?

A common message behind new abattoir proposals is that the rationalisation that has occurred in Australia’s meat processing network has left regional gaps that have created opportunities to rebuild, and to take advantage of recent technological advances to drive new efficiencies.

Interviews with proponents of individual projects over recent weeks have identified a range of motivations behind the various proposals including:

– The perception that greater competition is needed in slaughter markets, a common theme of producer input to industry focused-Senate inquiries between 2013-2017 and the 2017 ACCC cattle and beef market study (In its assessment the ACCC found ‘typically close competition’ exists for prime cattle in most regions, with exceptions including NQ and Tasmania – see more from its report in this separate article);

– The view that higher transport efficiencies and animal welfare benefits can be achieved by processing livestock closer to where they are produced, and transporting chilled or frozen meat, instead of cattle or sheep, longer distances by road to consumer markets and export ports;

– The potential to harness new technology including automation and renewable energy in new purpose-designed greenfield plants to achieve greater labour, energy and water-saving efficiencies;

– An opportunity to satisfy growing demand for more service kill capacity from the increasing number of dedicated supply chains and new beef and sheepmeat brands. MLA figures show the number of MSA-licensed brands rose from 131 three years ago to 172 last year. The limited number of plants offering service kill capacity can mean some brand owners currently have to transport livestock significant distances to access required processing space;

– A number of proposals have been driven by local councils seeking to attract overseas investment, with a particular focus on China, to drive economic and employment development projects.

But the question remains: Can new abattoirs succeed in a trading environment that has seen so many recent closures?

The chances of success will clearly vary according to the specific circumstances of each individual proposal, with key factors including the ability of new developments to compete against incumbents or to find underserviced niches capable of paying premiums, and the extent of specialised processing experience and knowledge proponents either have or can access.

Some of the projects on the large list identified yesterday clearly tick more of these boxes than others, while some proposals could perhaps best be described as fishing expeditions for investment, in which relatively limited proposals have been publicly cast out through media in the hope of getting a bite from a big funding fish.

That all of these proposals have been launched leading into what has turned out to be one of the worst droughts in Australia’s recorded history obviously hasn’t helped the cause for attracting investment.

But beyond current seasonal and livestock and water supply challenges, some with significant experience in the processing sector say many of the new proposals are simply not realistic.

In today’s high operating cost, low supply trading environment, they believe a sound argument in fact exists that Australia needs fewer processing plants working more shifts.

Ross Keane has extensive experience in the livestock sector as a fourth generation cattle, sheep and goat producer, a livestock agent and a long-serving general manager livestock for major processor AMH (now JBS Australia). He has also served the industry nationally as the independent chairman of the Red Meat Advisory Council and SAFEMEAT.

Ross Keane has extensive experience in the livestock sector as a fourth generation cattle, sheep and goat producer, a livestock agent and a long-serving general manager livestock for major processor AMH (now JBS Australia). He has also served the industry nationally as the independent chairman of the Red Meat Advisory Council and SAFEMEAT.

In the current environment Mr Keane says a new plant built to suit a boutique market could have a chance of succeeding, providing it is able to capture a premium that is large enough to offset the dearer costs of processing each animal in a smaller plant.

A key challenge in the current environment is available livestock supply.

It is several years since the Australian cattle herd last peaked, and the percentage of females being processed still exceeds 50 percent of total weekly kills.

Mr Keane predicts it will be at least a decade before the herd can return to anywhere near the 30 million mark again.

At the same time, Australia’s sheep numbers have plunged from 180 million in the early 1990s to about 70 million today.

Feedlots have helped to even out seasonality challenges in the cattle industry, but must be located in the grain growing areas to operate efficiently and consistently, he pointed out.

‘For one to succeed, at least one will have to close’

Mr Keane noted that most of the planned new abattoir projects propose to operate at a capacity of 500 to 2000 head per day.

He predicts that if these proposals go ahead, the end result will be either:

- The new plant will be superior in cost to operate than an existing plant in the area, so it will survive, and the old plant will close; or

- The new plant will not be able to compete against the existing plant for a variety of reasons including reputation (solid payment reputation), location (for cattle and labour supply), efficiency (labour saving devices etc), access to port, among others, so the existing plant would stay and the new plant would be mothballed.

“Examples of this would be if a new big plant is built in North Queensland, and it is efficient and reliable, then pick which one of the existing plants must close,” he said.

“Or if a proposed 2000 head per day plant is built on the Darling Downs, and is efficient, then at least two of the current plants will close.

“Really, what do we gain by doing this?”

“Most existing plants today have an upgrading program in place, and only the better located plants are left, so it makes more sense to improve those facilities,” he said.

He believes the focus should be on improving the capacity of existing abattoirs by utilising labour saving technology and installing enough additional chiller and freezer capacity to enable existing plants to work a longer span of hours, and provide flexibility for available livestock supply.

“Currently Kilcoy is the only seven-day a week plant that I am aware of, and it is still upgrading to a double shift seven days a week,” Mr Keane said.

“A smarter move might be the existing operators get together to build a ‘super plant’ that is more internationally competitive, and different operators operate different shifts etc, but that probably won’t happen due to the competitive nature of our industry and ACCC issues.”

Another pre-requisite he believes a new abattoir needs to succeed is sound port access, particularly given that more than 70 percent of Australia’s beef production is exported.

This may come as a surprise but all meat processed for export in Queensland is currently exported for economic reasons through the Port of Brisbane.

This includes meat processed at plants much further north in close proximity to other export ports, including Townsville, Mourilyan (Innisfail), Mackay, Rockhampton and Gladstone.

Freight rates mean it is still more economical to deliver meat from NQ and CQ to the Port of Brisbane to load onto the large container ships for export.

While many of the new projects have received favourable media coverage suggesting each is likely to go ahead, Mr Keane said a large number of the proposals he has seen come forward do not appear to be realistic, particularly in their estimated total costs to build.

“Meeting compliance for noise, odour and environmental regulations is often overlooked I suspect,” he said.

He also added that striking the right balance in scale between size, livestock availability and operating efficiency was a key challenge for new proposals.

“There is always a fine line to tread,” he said.

“Bigger throughput can often lessen your fixed costs, which reduces the per head or per kilogram cost to operate.

“Versus that, the more you kill, the more you need to buy, and often you give up the saving in the cost to operate with the premium to buy the numbers.

“Big throughput plants are good when you have a plentiful supply of cattle, but can be a headache when livestock numbers are short.”

Competition a critical driver of innovation for industry: producer

Competition was an important means of driving innovation throughout the industry, Central Queensland cattle producer and Cattle Council of Australia northern independent director David Hill said.

Any investments that fostered innovation and helped to capture added value and premiums for quality meat should be welcomed, he said.

Mr Hill said the industry has historically tended to focus on a high throughput, minimal-margin approach and economies of scale.

Mr Hill said the industry has historically tended to focus on a high throughput, minimal-margin approach and economies of scale.

But higher costs of production compared to other beef exporting nations meant Australia could not compete in export markets on price, and nor could it compete against cheaper proteins in the domestic market on price.

Examples of innovation to capture value included the ‘boutique-scale’ custom-plant to be built by Blair and Josie Angus near Moranbah, which will feature a cellular design to enable bespoke processing of individual animals to precise specifications, rather than a chain approach.

The larger processing companies were also innovating, he said.

“Look at what Teys are trying to do, for example, and the research they are doing at Lakes Creek.

“They are looking at the potential of automation to improve compliance to customer specifications and have a consumer ready product that is packaged in a way that doesn’t impact on eating quality and can extend shelf life, which is improving efficiency and adding value.”

He said talk of moving away from ‘a commodity approach’ had been around for some time, and there had been examples of this happening, but it now seemed to be gaining momentum as a real focus.

The approach of maximising the potential value of the product, especially for the consumer, was critical, he said.

“Value can be a point of difference as well as price,” he said.

“It would be to the detriment of the future viability of this industry if all value chain participants weren’t prepared to invest in future opportunities because of the belief that they could be unlikely to see a return that would warrant the risk.

“There will always be a level of competition, be it between red meat sectors, or, the big one at the end of the day, filling space on the consumers’ plate.

“A quote about competition I read recently said ‘the best part of competition is that through it we discover what we are capable of-and how much more we can actually do than we even believed possible’.

“Competition will drive innovation.”

HAVE YOUR SAY