TENS of millions of sheep in Australia could be at risk of compromised welfare from short-docked tails, according to the results of a recent survey and previous research.

TENS of millions of sheep in Australia could be at risk of compromised welfare from short-docked tails, according to the results of a recent survey and previous research.

The results of a national sheep producer survey published in CSIRO’s Animal Production Science publication this month indicated that short tail docking remains a sheep-welfare issue for Australian sheep, and that a knowledge–practice gap exists for some producers.

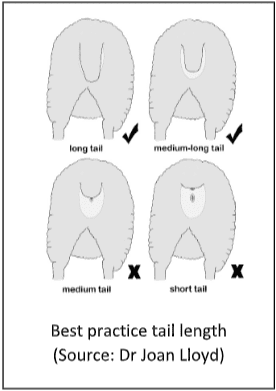

According to research, for docking to provide the optimal benefit, tails should be left at a length that covers the vulva in ewes and to an equivalent length in males. Docking tails shorter than recommended increases the risk of perineal cancers, arthritis and prolapse. Research indicates that some producers dock tails shorter than recommended, up to 57 percent in surveys and up to 86pc in on-farm data. The study aimed to ascertain the current tail docking length, practices, knowledge and attitudes of Australian sheep producers.

The survey found that more than half of the participants indicated that they docked tails shorter than recommended, either by image choice or contradicting length descriptions, the longstanding issue of short tail docking remains a welfare concern for the Australian sheep industry, the authors said.

A proportion of participants was unaware of and/or unable to accurately describe the recommended length and a level of incorrect short-length descriptions that were said to be long enough to cover the vulva.

The researchers said tail docking remains a relied-on practice for reducing the risk of flystrike, therefore ensuring that producers are supported to dock tails at the optimal length for sheep welfare is relevant and important.

“The results of this study highlighted that there is still research required in this space to better understand why some producers are docking tails shorter than recommended, to ensure successful extension for improved tail docking length and sheep welfare.”

For practice-change research, the researchers said industry extension and outreach, the multiple and varying factors contributing to short tail docking length need to be integrated and accounted for.

“The finding that approximately a quarter of participants did not know and/or could not accurately describe the recommended length elicits concern that the established optimal length has not reached or been adopted by a significant proportion of producers, yet there is hope that awareness could be raised.

“In this case, although we acknowledge that knowledge is not the only factor in achieving a higher-welfare tail docking length, it is an important finding to inform future research and industry-wide change,” the researchers said.

Their report said the multiple ways in which tail length was described by participants and the frequency of contradictory descriptions reflect previous research into the inconsistency and variation of how tail docking length and the recommended length are described by producers and industry publications.

“Although having multiple tail length descriptors is useful for both practice and research, it is important that the joint, length and other such descriptions are accurately representative of a tail that covers the vulva of ewes and to an equivalent length in males.

“These results further demonstrated that knowing that it is recommended to cover the vulva, what that looks like in practice and having accurate alternative measurements or descriptors may be key elements in being able to achieve it and should be considered for future research.”

The researchers said although the recommended tail length was not perceived to affect shearing or crutching, the attitude that shearers prefer shorter tails may be indicative of an ongoing level of influence and impact on tail docking practice.

“The existence and level of this potential barrier to docking tails at the recommended length will vary among individual producers and regions, and, as such, would need to be considered in the development of any extension strategy.

“Furthermore, depending on enterprise focus and mulesing status, who should be involved in extension and education should be considered and tailored, such as the involvement of contractors for mulesing enterprises and lamb-marking helpers and/or family members for non-mulesing enterprises.”

In our experience, when a lamb is upside down in a cradle with more underside of the tail visible, it looks appropriate to put a ring on too short. When the tail comes off and viewing the tail from behind with the lamb upright, it becomes more obvious the tail has been detached too short. We have needed to consciously apply the ring longer than it appears to end up at the correct length.

In our experience, the adult ewe needs to be capable of wriggling the tail. This slightly longer remaining tail stops any accidents at crutching and shearing to damage the vulva. Any damage to the vulva ends in lack of control for the ewe to shake any dribble clear. The short tail — whether it is a natural short tail or a short tail left after docking — can be held up, clear of faeces and urine. In all cases there has been less dags with a slightly longer tail docked or a natural short tail.

#WeLoveOurSheep

I can tell you straight up that

A/ there are only a few medical circumstances when (only) ewes’ tails should be shortened and

B/ the extreme case scenario shown in images 3 and 4 is the rule, not the exception in the sheep industry.

Guess what sheep use their tails for… swatting flies away before they lay eggs which culminates in fly-blown crutches.