Attacks by Iranian-backed Houthis from Yemen on commercial vessels passing through the Red Sea – one of the world’s most important maritime channels – have made ship owners reluctant to sail via the Suez Canal and Red Sea in trade between the Asia-Pacific region (including Australia) and Europe.

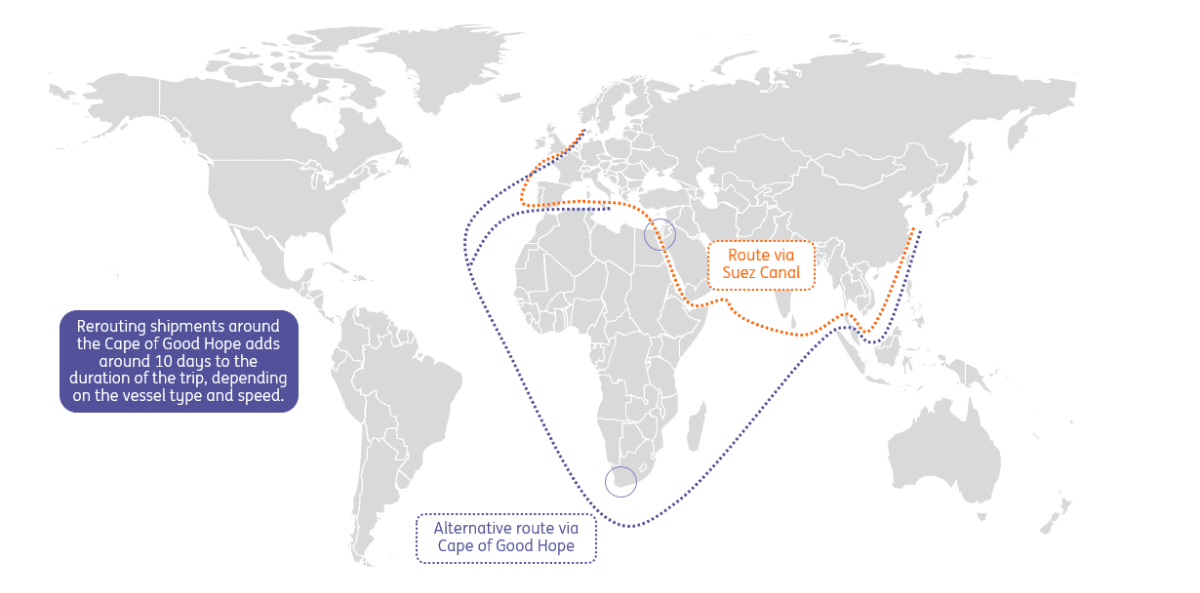

Instead, they’re choosing the longer and more expensive route via South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope (see map), adding about ten days’ sailing time to a typical cargo vessel voyage.

The Panama Canal dividing North and South America is not a viable option, being 40 percent longer in distance, in connecting the Asia-Pacific region with Europe.

One of the largest shipping companies has this week told its Australian export clients a further $500 will be added to charges on 20-foot containers and $1000 to 40-foot containers on the route.

Some container rates have now tripled since the Red Sea security crisis started in October. Rates have not yet hit the record highs seen during the Global Pandemic in 2020, but are trending in that direction, users told Beef Central.

The disturbance is also adding weeks to delivery times, in an already long sea voyage. The higher shipping costs will have to be either passed on to customers, or absorbed along the supply chain, one stakeholder said.

For Australian red meat exports, the primary export destinations impacted by the Red Sea crisis are the Middle East, European Union and the United Kingdom. Live cattle exports are also being impacted. Talk is also emerging this week of container shortages.

Attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea have recently intensified, and there doesn’t appear to be any sign of tensions easing yet.

In the last three weeks of December, 80pc of the container vessels on the Suez route were forced to change course, reaching 90pc in the first week of January, according to shipping intelligence network, Clarkson.

Largest container freight operators MSC and Maersk diverted more than 60 vessels around the Cape in just three weeks, while other container lines including Hapag Lloyd, Cosco, ONE and Evergreen have taken similar action.

With 12pc of global trade, including billions of dollars in Australian exports and imports passing through the Red Sea, Australia has a direct interest in safeguarding the passage.

A British Chamber of Commerce trade expert suggested about 500,000 containers were going through the Suez canal in November, before dropping to 200,000 in December. He quoted rates on containers that cost US$1500 in November rising to $4000 in December.

“If things get worse, it only adds to the disruption, and the cost of containers will go up and global trade will fall further,” he said.

A Word Bank report on the crisis said recent attacks on commercial vessels transiting the Red Sea had already started to disrupt key shipping routes, eroding slack in supply networks and increasing the likelihood of inflationary bottlenecks.

Energy supplies could also be substantially disrupted, leading to a spike in energy prices, the World Bank report suggested.

“This would have significant spill-overs to other commodity prices and heighten geopolitical and economic uncertainty, which in turn could dampen investment and lead to a further weakening of growth.”

“There are also potential indirect impacts from the Red Sea attacks on agricultural markets. If they persist and lead to increased delays, farmers could see their input costs increasing… in the form of higher diesel prices and potentially higher fertiliser prices,” the World Bank said.

As if one global trade route issue was not bad enough, the alternate Panama Canal sea-freight route between North and South America is facing its own challenges, firstly through congestion, and secondly due to local drought lowering the canal’s water levels to the extent that some deeper-drafted ships are unable to complete the passage.

Impact on Australian agriculture

RaboResearch general manager Stefan Vogel.

Rabobank offered the following summary on the escalating Red Sea crisis this week:

Trade logistics are set to become increasingly challenging for Australia’s agricultural sector with the escalating tensions in the Red Sea disrupting global trade.

However there are also potential upsides for the nation’s wheat and barley exports according to Rabobank.

RaboResearch general manager Stefan Vogel said as ocean shipping companies divert more vessels away from the Suez Canal to avoid attacks by Houthi militants and the escalating military action against them in the Red Sea, Australian canola exports may be particularly impacted as the bulk of these are destined for the EU and normally shipped through the canal.

Australia may also have to deal with some increased costs for imported goods – such as certain fertilisers, ag chemicals and machinery parts – as importers face higher freight costs, as a result of diverting around the canal and impacted areas. However, the elevated freight costs are not expected to reach the Covid-related highs seen in 2021.

“Globally, for containerised and bulk goods, the shipping industry has to make tough decisions at the moment – either to navigate the Suez Canal and risk severe attacks by Iran-backed Houthi rebels or to take a nine to 15-day detour around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope,” Mr Vogel said.

Mr Vogel said initial attacks by Houthi rebels on cargo ships had seen bulk freight rates spike in December.

For Australian canola exports, shipments to “our prime markets in Europe are likely to get more complicated and expensive”, he said, “as they do usually pass through the Suez Canal, while canola shipments to the EU from our competitors in Ukraine and Canada do not.”

Conversely, Mr Vogel said “the canal issues might help Australian wheat and barley shipments to be slightly more competitive into destination markets in Asia, the Middle East and eastern Africa.”

“This is because our key competitors from Russia, Ukraine, the EU and even the east coast of the US will struggle to get to these destinations as they usually pass through the Suez Canal, while Australian grain does not,” he said.

The impact of the Suez/Red Sea crisis on agricultural fertiliser and other farm input imports is likely to be mixed, Mr Vogel said.

“Fertilisers used on farm in Australia are largely imported in bulk. And, at least for nitrogen and phosphate fertiliser supplies, they should not be impacted much as they mostly derive from Asia and the Middle East and don’t pass through the Suez Canal,” he said.

“Potash, however, largely comes to Australia from North America and Europe and some of those shipments could be impacted by the attacks and re-routing of vessels.”

Containerised shipments – both to and from Australia – will also be affected, Mr Vogel said.

“And this is likely to have time and cost impacts on plant protection chemicals and machinery parts coming into Australia as well as Australian meat and fresh produce exports,” he said.

“During the 2021 freight crisis, Australia struggled to find sufficient containers for exports as shipping companies gave preference to their major global routes and somewhat neglected Oceania or they tried to quickly take empty containers back from Australia to China rather than adding in shipping time to export Australian goods. A similar struggle for containers is not unlikely to materialise again if the Red Sea struggles tighten global container freight capacity further.”

The FBX global ocean freight container index has more than doubled from early December to mid-January to reach the highest price level seen since October 2022, Rabobank said.

“The good news is container freight rates at the moment are still three to four times below the massively Covid-inflated levels of 2021,” Mr Vogel said.

“Imported goods into Australia will have to bear the higher freight costs, but container freight is unlikely to get as expensive as in 2021.”

RaboResearch global economic strategist Michael Every said while “things aren’t as bad as the last shipping crisis, they could still get painful if the Suez/Red Sea crisis is not resolved soon.”

And total container transits and tonnage via the Suez Canal have now slumped to Covid-era lows, he said.

“Helpfully, ocean carriers have added 11 percent container ship dead weight tonnage capacity since Covid,” Mr Every said.

More broadly though, he said, the current “Red Sea/Suez crisis, on top of the ongoing Black Sea/Ukraine crisis and the risk of others to follow, provides a fat tail risk of potential fresh waves of inflationary supply shocks for western economies and financial markets, which are currently predicting nothing but easing price pressures and large rate cuts in 2024.”

HAVE YOUR SAY