AUSTRALIA currently did not have enough government staff to manage a year-long Foot and Mouth Disease or Lumpy Skin Disease outbreak, a senior government biosecurity officer said this week.

In an FMD/LSD webinar on Wednesday, head of DAFF’s National Animal Disease Taskforce Dr Chris Parker was asked whether there was enough government staff to manage a disease outbreak.

Dr Parker said the taskforce was in the process of looking at “what our workforce looks like and what workforce is available.”

He said there 180 Commonwealth veterinarians working in plants would become available and there are State Government and private vets.

“So there is a range of these things that are being worked through at the moment.

Dr Chris Parker: “No, I couldn’t…”

“Could I put my hand on my heart and say ‘we could manage a year-long outbreak?,” he said.

“No I couldn’t, but what I can do is say that that workforce is being understood, gathered together and trained to ensure that we do have the resources that are required.

“It is something that we are really quite concerned about.”

Dr Parker said Australia would run an exercise called Exercise Paratus, based on an FMD outbreak scenario.

“I think that will help highlight some of these issues around where staff might be, where they might be required and how many might be needed.”

Webinar participants were told that to retain access to global premium red meat markets Australia needed to maintain its Foot and Mouth Disease status without vaccination “at all costs.”

Meat & Livestock Australia’s manager of global trade development Tim Ryan also said an updated ABARES analysis showed the multi-state Foot and Mouth Disease control costs would be dwarfed by the $80.3 billion export revenue impact across all agri-exports over 10 years.

National Farmers Federation chief executive officer Tony Mahar, a member of the LSD/FMD Taskforce’s trade and protocols working group, said that a recent government taskforce found Australia’s preparedness in the event of an exotic animal disease outbreak is “sound and strong.”

“But we also know that the threats and risks are increasing.

But he said the risks of an LSD or FMD incursions were low – 28pc for LSD and 11.6pc for FMD – based on structured expert judgments made in June this year.

He said the total value of Australia’s agricultural production is about $86 billion and the value of exports this year is expected to be a record $70 billion.

“So in anyone’s language, what is at stake here is a large proportion of the GDP from agriculture.”

Mr Mahar said ABARES’ recent estimate of the impact of a multi-state FMD outbreak over 10 years of $80.3 billion was conservative and “a starting point” and the cost would depend on the context of an incursion.

Trade impacts have been under-estimated

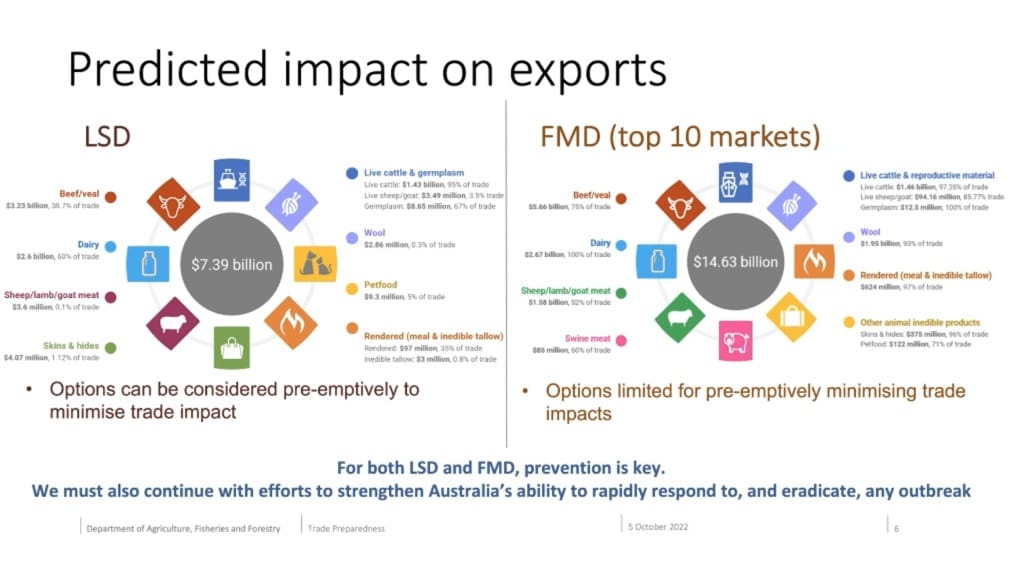

The Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries acting first assistant secretary exports and veterinary services division Tom Black outlined the predicted impact of FMD and LSD on exports. He explained that the department’s estimates of the trade impacts were conservative.

He said DAFF had been reviewing the export requirements relating to FMD and LSD to assess what trade would be impacted, ie immediately suspended.

A change to Australia’s health status on FMD or LSD would have major impacts and a broad range of commodities meat, dairy, skins and hides and wool, pet food and rendered products, live animals and their reproductive material would be affected, he said.

“The extent of impact certainly differs between commodities though.

“So if there was an incursion of either LSD or FMD, we understand the trading partners might react differently to what we anticipate and/or place unexpected bans on other exports as well,” he said.

“We think we’ve got a pretty good handle on it, but we just don’t know trading partners may react for some of the commodities that may be a bit of left-field.

“So again, we think the trade impacts are likely an under-estimation at this point.”

Mr Black said it estimated that an LSD incursion could have an impact on Australia’s top ten markets of $7.39 billion annually, and although this is less than the FMD figure — $14.63 billion – DAFF has already started working with trading partners to minimise the impacts, as agreed at a July workshop.

He said last week the department led a workshop last week to discuss impact analysis and a strategic approach of preparing our exports in the event of an FMD outbreak. Mr Black said the $14.63 billion annual impact estimate did not capture the entire trade.

“Nonetheless we are still looking at an enormous figure.

“For FMD though, the department is focusing our activities on preparatory activities to streamline our response to help regain trade as quickly as possible once an outbreak is under control,” he said.

“We think it is much more important that we are prepared in the case of FMD and much harder to be able to negotiate now with trading partners around FMD.”

He said his key message was that impacts or LSD and FMD are “really large, but the department is really work hard with industry to minimize and mitigate trade impacts in the event of an outbreak.”

Mr Black said post-incursion negotiations with trading partners would be difficult.

“Much better to stay free than end up in the space of having to negotiate back into markets.”

Australia must maintain its FMD-free trade status “at all costs”

Meat & Livestock Australia’s manager of global trade development Tim Ryan

Mr Ryan outlined the loss of access, reputation and premiums, and the timeframes, involved in returning to trade after an FMD outbreak.

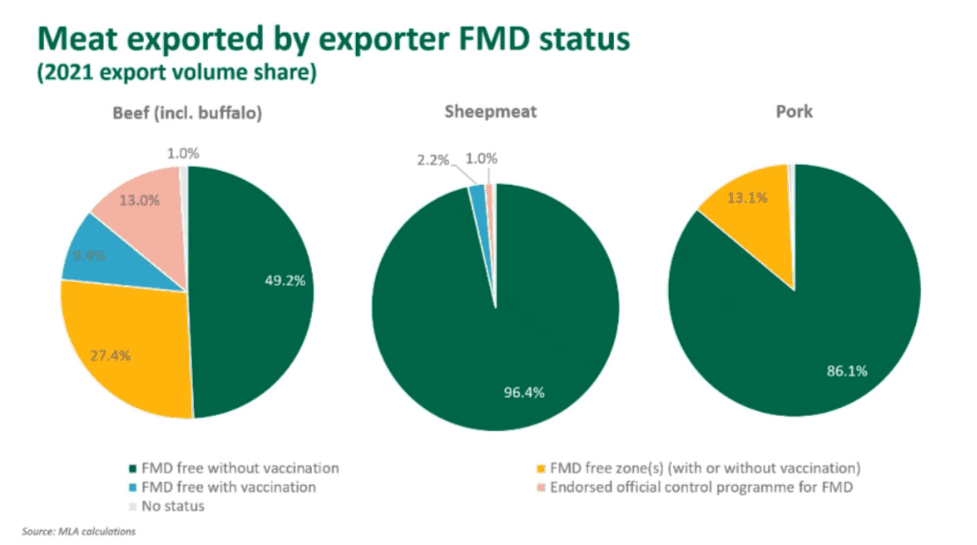

He said red meat is heavily export-reliant and export levels globally revolve around the FMD status of exporting countries.

“The main take home here is the vast majority of trade across the affected meat products (beef, sheep meat and pork) is from a country with an outright FMD-free without vaccination status.

This emphasized the importance of maintaining FMD-free status without vaccination, he said.

“There is trade that can occur outside of that (FMD-free no vaccination) status, however; either under a vaccination program, a zoning program or even an endorsed official control program.

“There is the potential for trade to take place, but that may be following fairly protracted and rigorous negotiations with the exporting and importing countries, so they are not saying they (exports) can be turned on overnight,” Mr Ryan said.

“So really what is critical for Australia is maintaining disease-free status and accessing those premium markets as such.”

Mr Ryan said showed that in 2021, 49.1pc of the world’s beef exports, 96.4pc of sheep meat trade and 86.1pc of pork exports came from countries with FMD-free without vaccination status. Significant beef and pork exports came from countries such as Brazil into Asia with FMD-free zones with or without vaccination, but did not have access to premium markets. He said about 13pc of world beef (incl. buffalo) meat exports was made up of Indian buffalo meat under an endorsed control program, but to fewer markets.

“So while trade can occur, it is quite limited and that’s on the back of fairly significant negotiations.”

The majority of sheep meat being traded under an FMD-free without vaccination status reflected that most exports are traded out of New Zealand or Australia and to a less extent Europe. He said the vast majority of live export trade occurs under an FMD-free without vaccination status, although livestock trade between African and Middle East countries takes place under a different status or no status.

“The main conclusion here is when it comes to trade and keeping premium markets we want to maintain that (FMD) free status at all costs,” Mr Ryan said.

Market premiums would be lost

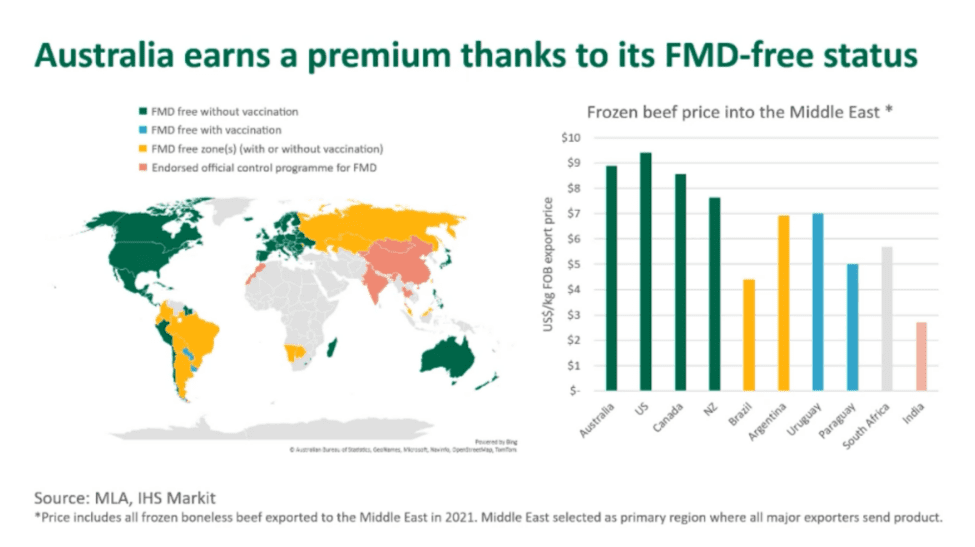

Mr Ryan said the other implication of a change in Australia’s disease-free status could be in the potential premiums earned on export markets.

He said last year Australia’s average frozen beef price into the Middle East at about $9/kg was a premium of about $2/kg or 20-25pc to product from Argentina and Uruguay.

“So there could be short and long-term implications for Australian exporters if we lost that status and consumers weren’t willing to pay such a high premium for our product in export markets.”

Mr Ryan said a recently updated 2013 ABARES analysis of the socio-economic impacts of an FMD outbreak quantified the cost at $80.3 billion over 10 years.

“The first thing I just wanted to flag is the actual control costs of addressing the disease are dwarfed by the impact on export revenue across Australia’s various agri-exports.

“Particularly knowing that beef and sheep meat would be the most affected, given their size and export exposure, but dairy, wool and a range of other commodities would also be affected by an FMD outbreak.”

Timeframe to FMD-free status is a key driver

Mr Ryan said another key driver of an outbreak’s impact was the period that Australian exporters might be locked out of premium markets.

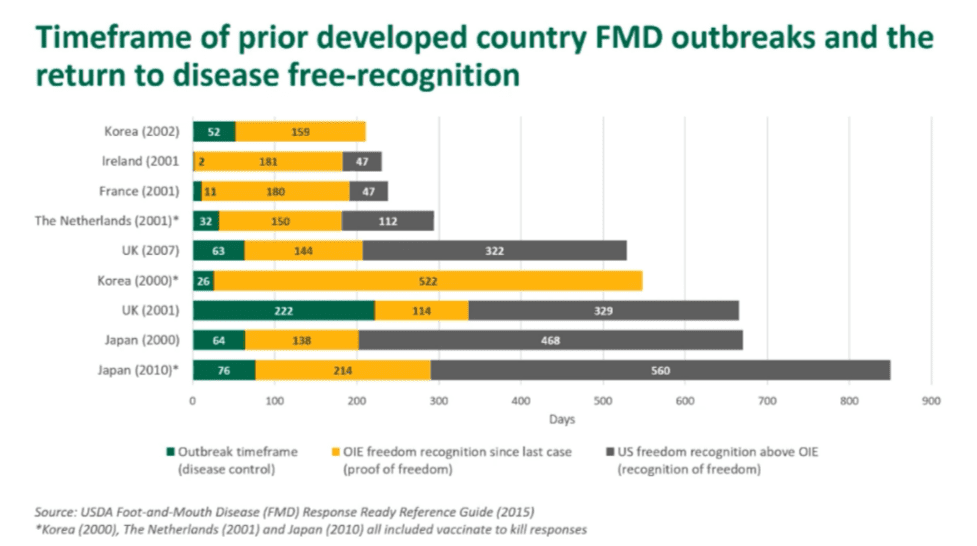

He said recent Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries modelling and simulations showed that timelines from the first FMD case to last cull could be up to 195 days, though mostly less than 30 days. The time to regain World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) freedom recognition after last cull would be at least 90 days. Mr Ryan said the United States has taken 47-560 days before bilateral recognition of freedom status after WOAH recognition occurs.

“Beyond that there could be other implications such as consumer demand or consumer concerns about our status as well.”

He said showed how the combined outbreak, WOAH and bilateral freedom timeframes varied for countries before the US granted access after recent FMD outbreaks.

“Given Australia exports to so many markets around the world there would also be quite a variability in how long each individual market, if they required additional checks in place, would take to recognize our freedom status.

Mr Ryan said after the 2001 FMD outbreak in the United Kingdom, sheep meat and pork trade collapsed in March 2001 and didn’t recover to stable levels until OIE FMD-free status was granted in January 2002.

“Even three years after the outbreak had occurred, trade had yet to recover to that pre-outbreak level.

“So there are lasting effects that we need to be mindful of when it comes to an outbreak such as FMD.”

Red Meat Advisory Council chair and webinar mediator John McKillop said Ireland took two days to control FMD and 181 days to regain status again.

“You would think that if you were think if you were that quick onto it and it was such a small outbreak that markets would forgive you.

“They did somewhat quicker than others, but it was still six months before they were able to get back in again.”

New outbreak risk assessments done, but no details

Dr Chris Parker said of course there are still animals with FMD in Bali, but the Indonesians were making a significant effort with vaccinations.

Cattle and smallstock were being vaccinated, with the help of Australia’s one million donated vaccine doses and there had been a lot of training of people in Bali, he said.

Australia had not changed its border settings in regards to Indonesia and Bali.

“There is still active infection in Indonesia and we have very stringent controls at the border that were upgraded a number of times and continue to be reviewed.”

Dr Parker said “of course” there had been recent outbreak risk assessments of likely pathways for an FMD outbreak via illegal meat imports and for LSD via vector/weather patterns, but he did not disclose what they were.

LSD not close enough to blow in

He said there had been work done on LSD “chances of entry”.

“It’s spread by a vector and it will spread to where there is cattle, so yes, there is likely to be slow spread of this disease as we’ve seen it through the rest of the world.

“Vaccination is an important component of it, and the control, and that will remain an important component,” he said.

“It’s important to point out that it is not close enough to blow in yet and we’re still getting a handle on exactly how some of the weather patterns work and where the likely places are where it would land.”

He said it needed to be considered that there were not a great number of cattle in Papua New Guinea, “so FMD would be more of a concern in PNG with the large number of pigs…”

“The other part we need to think about is, what stocking densities do we need in the north to get establishment and spread of these sorts of diseases in Australia, so there is quite a bit of work that needs to be done.”

The survivability of the virus on the mouth parts of a biting insect and the probability of the vector being blown by a cyclone into Australia also needed to be understood, he said.

He said the most likely ways of FMD getting in were through infected animals or meat, and making contact with a susceptible animal. Swill feeding and people returning straight to farms and not following appropriate biosecurity measures after visiting countries with FMD were a concern “and that’s where we put a lot of resources at the border.”

Dr Parker said LSD is not a zoonotic disease and FMD in very rare cases has been transmitted to humans from animals, with only about 40 cases worldwide.

“The messages we will be putting out is that product is safe to eat and drink, both LSD and FMD cannot be transmitted to humans through meat or milk or any of those sorts of things.”

HAVE YOUR SAY