The ability of sunspots and solar flares to influence weather is attracting interest as the drought continues. Image – NASA

INTEREST in non-conventional climate influencers is on the rise as conventional models watched by Australian agriculture continue to generate forecasts devoid of rain for drought-stricken areas.

Among them are sunspots, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) and Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW).

While none point to drought-breaking rain in coming months, they each offer their own explanations as to why the past two years have been the driest on record for central and northern New South Wales and southern Queensland.

Narrabri-based AgEcon partner and climate-extension specialist Jon Welsh said the interactions of all of them, including the best-known driver of eastern Australian climate, the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO), could allow some rain-bearing fronts into drought-declared areas towards the end of spring.

This is despite the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) saying in its most recent seasonal outlook that a wetter-than-average spring looked unlikely.

Looking for signs

Mr Welsh said the drought had people looking for signs of impending rain like spring-fed creeks starting to run, murrayas flowering and black cockatoos on the wing, and has renewed interest in sunspots as a driver of rainfall.

Even clairvoyants were being consulted by a handful of primary producers to predict the end to the current drought cycle which started in 2017.

“I’m spending a lot of my time these days fact-checking non-conventional theories from growers looking to make planning decisions around when the drought will break.”

Pacific factors

Some hope exists that the next weather phase ushered in by the decay of the current positive IOD phase, and the central Pacific-based El Nino Modoki, will allow some significant rain-bearing fronts into drought-declared areas.

“The strongly positive IOD is coming to the end of its evolution for summer-cropping areas in eastern Australia.

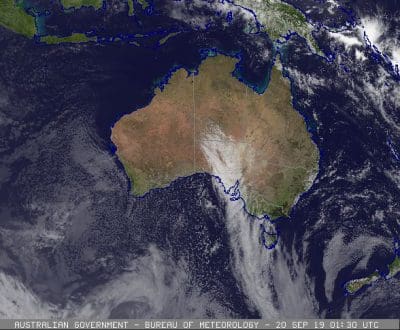

The latest satellite image from shows no cloud over drought-affected areas. Image: BOM

“Along with the El Nino Modoki, it’s been the dominant influence of our climate, also contributing to the strength and position of the high-pressure system over southern Australia, and it’s set to reduce as we come into September-October.”

Mr Welsh said historically in these years, statistics show the position of the sub-tropical ridge moves further south, and air-pressure patterns readjust to circulate moisture from the east into northern NSW and southern Queensland in the second half of spring,

“We’re waiting for this IOD to decay, and for high-pressure systems to move through eastern Australia instead of staying put.

“This is quite an unusual event to see a neutral ENSO and positive IOD, coupled now with stratospheric warming, so while those statistics are interesting, we seem to be living through new historical records and continually reading forecasts containing nothing but bad news.”

IOD influence

Mr Welsh said good late spring rain in eastern Australia was possible with a positive IOD in eastern areas, but the most of the world’s eight global operational climate models, including the BOM’s, where not forecasting significant rain events for spring at this stage.

Jon Welsh

Mr Welsh said summer months often see more local factors influencing weather, and they could bring much-needed rain to dryland summer croppers and dam catchments in irrigation valleys, which would benefit cotton growers.

“The MJO can unsettle the status quo, and lows from over the Coral Sea and Tasman Sea can come inland, but we would prefer to see the Southern Annular Mode swing positive to aid in this moisture flow into NSW at least.”

Mr Welsh said many rain-bearing systems are due to “completely random events”, which is why climate forecasts are always communicated in terms of probabilities.

“Those originating from an easterly direction have simply been non-existent this year, as evidenced by bushfires around Dorrigo, normally the wettest part of the NSW.

Mr Welsh said there was no one-to-one linear correlation between climate drivers and particular weather events.

“Those close to the science would acknowledge the complexity, and instances where theories and research have known shortcomings at certain geographies and times of year”

One example was Tropical Cyclone Debbie, which in March 2017 brought heavy rain to the Burdekin, Central Queensland and the Darling Downs, as well as the north coast of NSW.

No hope from space

Bendigo-based Kevin Long is behind The Long View long-range forecasts, and said reducing solar-radiation levels, or sunspots, have been a driver of the reduction in rainfall to current lows from high totals recorded between 1940 and 1980.

“The sunspot influence is part of the reason for the slow reduction of average decadal rainfall that started in the 1980s, and has resulted in the general 30-per-cent loss of average rainfall across eastern Australia since the 1970s.”

Mr Long said cycles in the solar system made the current drought “very predictable”.

“Only once every 297 years is the 18.6-year lunar-driven drought cycle fully enhanced by the 19.8- year synodic drought cycle of Jupiter and Saturn.

“This combination of two cosmic forces causes low rainfall for up to nine years, and the driest extremes occur nine to 10 years after the wettest extreme that occurred during 2010/11.”

Mr Long said cooler-than-average sea-surface temperatures in all Australian coastal regions, as well as changes to levels of Antarctic sea-ice, were also intensifying the current drought cycle.

“This drought is not primarily caused by the bicentennial solar minimum cycle that commenced about 40 years ago, but is rooted in the strongest combined drought forces seen in eastern Australia for 297 years.”

Mr Long said solar experts around the globe have forecast the dominating reduction of solar levels will continue for another 30-40 years prior to the next rising trend commencing.

“This drought will be worse than all the preceding droughts due to the combining of at least five natural drought drivers.”

BOM definitions

IOD: Sustained changes in the difference between sea-surface temperatures of the tropical western and eastern Indian Ocean. The IOD is one of the key drivers of Australia’s climate and can have a significant impact on agriculture.

This is because events generally coincide with the winter-crop growing season.

The IOD has three phases: neutral, positive and negative.

Events usually start around May or June, peak between August and October, and then rapidly decay when the monsoon turns into Australia’s wet season around the end of spring.

Eastern Australia’s most recent bumper winter-crop year, 2016, was a negative IOD year.

MJO: The major fluctuation in tropical weather on weekly to monthly timescales. The MJO can be characterised as an eastward moving pulse of cloud and rainfall near the equator that typically recurs every 30 to 60 days.

If one took the time to do the mathematics of the solar system rotation (ie) Mercury to Pluto (ie) earth 365 days to orbit the sun and Pluto 144 etc, you could see just how the earth changes.

Remembering all the planets aligned in 2012, so with the lead-up and departure you could predict the next cold phase. By the same token, pollution is like smoking.