DEBATE is raging about the legitimacy of the new soil carbon industry after a handful of Australian producers broke new ground last year with large-scale issuances of soil carbon credits.

Australia’ soil carbon market, which enables producers to be financially rewarded for improving practices, has been described as a source of envy by farmers in other parts of the world, such as Europe and New Zealand, whose Governments do not enable them to receive credit for the carbon stocks they store.

But not everyone in Australia is happy with the current policy approach.

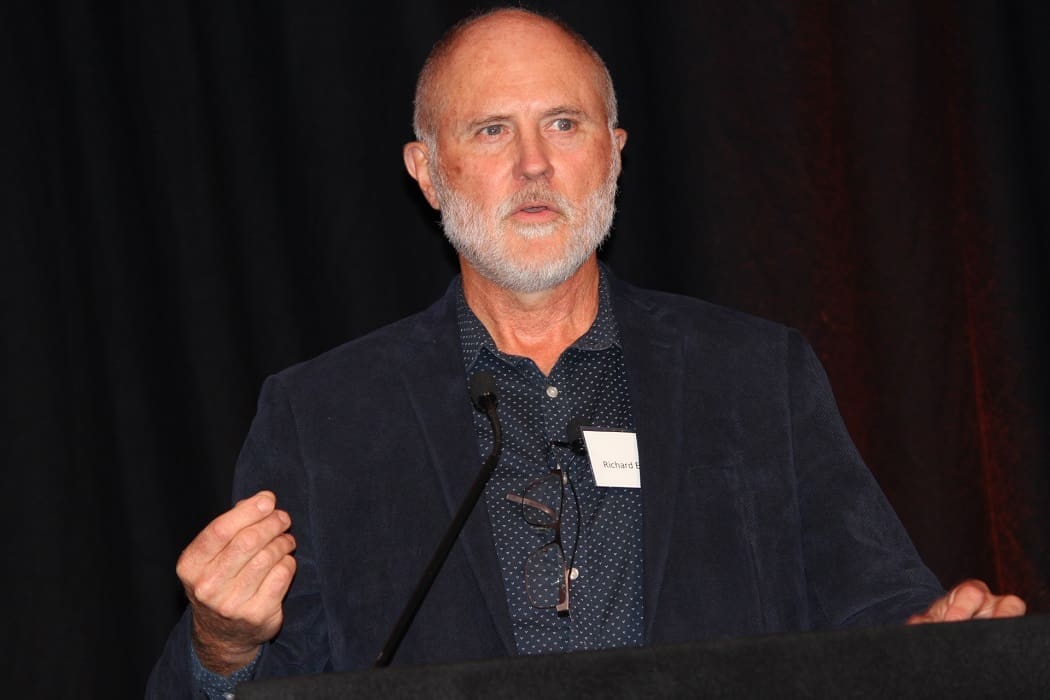

The recent issuances of large numbers of Australian Carbon Credit Units to several producers have been criticised by a group of scientists, including University of Melbourne professor Richard Eckard, who has been at the forefront of agriculture’s work to adapt to and mitigate the potential impacts of climate change.

They claim the increases in soil carbon for which farmers received financially valuable credits are more likely to have come from increases in rainfall than from their own changes in management.

They have also raised concerns about a lack of transparency from the industry regulator and have expressed the belief that the current policy rewards farmers financially for doing work they were already going to do.

The tensions were clear at the recent field day at Wilmot last month, a Northern NSW property which made global headlines for a pioneering sale of soil carbon credits to Microsoft in 2019.

Wilmot general manager Stuart Austin told AgCarbon Central the farmers who were issued ACCU’s had shown real fortitude by investing in soil carbon projects and had done everything asked of them.

“As early adopters in an emerging market, these guys have taken on the risk and have been subject to the highest level of rigour,” he said.

“It took 18 months from the last round of soil tests until the issuance of ACCUs, they were audited multiple times, they have complied with all the rules, endured three methodology changes, and there are some who are still questioning their validity.”

Who should have the data?

Last year three projects run by CarbonLink were issued a combined 245,578 ACCUs for the first five years of their soil carbon projects. They are now required to keep that carbon in the soil for the next 20 years and will be issued more if they continue to sequester carbon.

“We are in a situation now where we have the most comprehensive dataset on soil carbon in intensively managed grazing systems, across the widest area, over the longest time period and to the greatest depths, that I know of anywhere in the world” Mr Austin said.

“Understandably, scientists are saying ‘show us the data’, however you have to consider the millions-of-dollars it has taken to collect it, the risk the producers have taken and the criticism they have already endured.

“We need to learn more about SOC at depths beyond 30cm in grazing systems off the back of these successful projects.”

While decisions are currently being made about the sharing of the CarbonLink data, it must be said the scientists have suggested they analyse the data under strict non-disclosure agreements.

One of the CarbonLink producers put an open invite to scientists to visit her property and work through the issues on AgCarbon Central last year. QUT is doing its own testing on another property, which was issued ACCUs last year.

Wilmot also shared the data from its deal with Microsoft in 2019, by making it available online. The same group of scientists raised concerns about the methodology it used to generate those credits.

“We made that information public because we wanted to show the rest of the industry what could be done and how much potential there was,” Mr Austin said.

“Australia’s carbon market is the envy of the world and the achievements of the landholders who were awarded ACCUs last year should be recognised, respected and applauded.

“However, frustratingly there is still a view that ‘soil carbon can’t be done’.

“We know that managed grazing with deep-rooted perennials enhances long-term soil organic carbon storage. Australia has a unique combination of a well-developed, well-managed livestock grazing sector and a vast area of available rangelands on which to apply grazing practices that support soil carbon sequestration.

“We have a real opportunity right now to demonstrate how the red meat industry can be part of the climate solution.”

At the recent Wilmot Field Days, AgCarbon Central asked the executive chair of Macdoch Australia which owns Wilmot, Alasdair Macleod, for his thoughts about the recent criticisms.

“I’m confused by some of the criticism; some are suggesting that sequestration is mainly achieved as a result of increased rainfall, but the evidence from the Carbon Link projects suggests that this is not the case. Others are suggesting that farmers shouldn’t be encouraged to sell carbon credits, even though there is an opportunity to enhance farm income, as well as building climate resilience,” Mr Macleod said.

“We need to encourage more producers to get involved with soil carbon projects and share data from those projects widely, so that we can better understand the relationship between good grazing practice and sequestration of carbon at depth.

“The success of the Wilmot Field Day this year is testament to the fact that there is plenty of ongoing intertest in this space. For Macdoch, ensuring ongoing engagement with a wide range of stakeholders, including the scientific community and wider supply chain, remains a priority.”

What is the priority for the scientists?

Getting access to the data collated by the soil carbon companies appears to be the main priority for the scientists.

Professor Eckard told AgCarbon Central the Government audits did not factor in rainfall over the reporting period – whether it was above or below average.

“The audits they talk about are numerical not biophysical audits. The Clean Energy Regulator just wants to make sure that they have followed the protocol, so the audit focuses on how many soil samples they took, to what depth, was the Lab accredited etc,” Prof Eckard said.

“There is no independent audit to gauge whether the atmosphere benefited, through independent verification.”

Asked whether the carbon sequestration measured in the soil demonstrated a benefit to the atmosphere, Prof Eckard said it did, however, it did not work out how much of the sequestration was a natural process and how much was management.

“Any change in soil carbon has to come out of atmosphere, that is true,” he said.

“I am convinced that many of the properties claiming increasing soil carbon have achieved a positive change in the soil organics – our only reservation is the magnitude of their change, as our data shows 70pc of the change in soil carbon can be attributed to rainfall. In other words, carbon might have gone up but you should not get paid for it if it was just rainfall and not your management.”

The current carbon market has measures to safeguard itself from issuing credits that have happened as a result of rainfall. It makes producers prove they have changed their practices, it requires them to keep carbon in the ground for 25 years and holds back 25pc of the credits it has issued in case soil carbon levels go backwards.

Asked what the issues were with these measures, Prof Eckard said it was more about verifying the data with

Prof Eckard said he believed there will be losses in soil carbon in the future.

“We have two peer-reviewed papers that suggest climate-change itself will make sure the loss in carbon is there,” he said.

“Will these soil carbon companies exist in 10-years-time or will it all be put back on the farmer? We don’t have any confidence that anyone will take responsibility for the loss.”

For a view about soil carbon trading in the European Union readers might like to read “Carbon farming: Are soil carbon certificates a suitable tool for climate change mitigation” by Carsten Paul et al published in the Journal of Environment Management, Volume 330 March 2023, which is available to download. On soil carbon increase permanence these scientists concluded “The build-up of SOC is fully reversible and typically slow in and fast out …permanence of SOC sequestration cannot be guaranteed.” This supports the evidence from many Australian soil scientists.