Tea from a thermos at the Wulatehou Cashmere farm, from left, farmer Bai, Mr Zang, Peter Small, Sydney Wang and Mr Xie.

KNOWING nothing about cashmere other than it came from a goat, I have always been fascinated and eager to learn more about this luxury fibre.

And so the opportunity arose, when last year my great friend Ya Jing Wang, known as Sydney Wang, invited me to go with him to Inner Mongolia.

Sydney, a young executive with Xinao, a Chinese Textile company in Zhejiang Province, is responsible for sourcing cashmere fibre for his company and also for Todd and Duncan, the famous Scottish textile company in Scotland, recently acquired by Xinao.

On May 7 2024, together with my good friend and fellow Australian wool grower, John Cordingley, I flew with Sydney from Hangzhou International Airport in Zhejiang Province to Yinchuan near the border with Inner Mongolia in Northern China, a distance of nearly two thousand kilometres.

In Yinchuan we were met by two cashmere collectors Mr Zhang and Mr Xie, who were to be our guides for the visit. Mr Zhang and Mr Xie have the relationships with the cashmere farmers, they know the area, the farms and what is going on with the market and where shearing is underway.

From Yinchuan we worked our way north to Bayannaoer, a distance of over 300 kilometres visiting three cashmere farms that were shearing; – “Pingluo” owned by Mr. Wu and his family, “Hangjinhou” owned by Mr Zhang and “Wulatehou” owned by Mr Bai and his family.

All these farmers were extremely welcoming and generous, inviting us into their homes to enjoy tea or a selection of fresh fruit, particularly water melon that was obviously in season.

At each of the three farms shearing was underway. When we arrived at “Hang- banner” farm, the farmer Mr Zhang was bringing his best cashmere buck forward for shearing. He was indeed a handsome animal.

A cashmere sire.

Key features of the cashmere goat are wide horns, displaying beautifully white exterior fibres. These exterior fibres are long, coarse — 32 microns-plus – and referred to as wool or hair. These outer fibres an Australian wool grower would recognise as the primary fibres. The valuable fibre on a cashmere goat is the down, the shorter finer 15 to 19 micron fibres next to the skin. These fibres, on a Merino we would recognise as the secondary fibres; on goat this is the valuable cashmere.

After centuries of careful selection and breeding with the Merino, particularly in the last 200 years, it is impossible to identify the primary and secondary fibres with the naked eye, the primary and secondary fibres can only be identified by examining the skin follicle formation under a microscope.

Once shorn the complete cashmere fleece is packed into bags and sent to a factory for what is known as de-hairing; the removal by machinery of the stronger outer fibres, the hair or wool, from the shorter finer fibres near the skin, the cashmere.

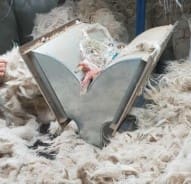

Shearing cashmere goats.

Shearing is done in the corner of a pen.

On arrival at the dehairing factory from the farm, the fleece is removed from synthetic bags, previously used for fertilizer, feed etc. themselves sources of contamination.

Contamination is removed form the cashmere.

The raw fibre is sorted five times by women, who are mainly looking for contamination. Every sort contamination is found; plastic bags, binder twine, bits of cotton – an unbelievable assortment.

Each of the five women sorters has a tray in front of them to throw contaminants. In the photo below to the left can be seen the hand of a sorter with a mounting collection of contaminants. Despite the dedicated work of the sorters, contaminants still goes through to the final product.

Careful examination of the photo will show the long coarse hair and the shorter finer fibres, the cashmere. These fibres are still to be separated mechanically before scouring, blending and dyeing. The cashmere then goes through the same process as is used in the wool trade for carding wools, known as woollen spun.

Cashmere goats grazing rangelands Inner Mongolia. Herds usually return to the farm yard in the evening for supplementary feeding.

Economics of Cashmere Production

Knowing that cashmere is the luxury fibre, bringing a substantial premium on the retail shelves around the world, two Australian wool growers could not but be interested in the return the farmer receives for producing this wonderful fibre.

Once the fibre from shearing has been de-haired, each cashmere goat produces about 150 grams of pure cashmere. Depending on the assessed micron, the farmer is paid around US$85 a kilogram. That is to say it takes six or seven goats to produce a return of US$15. The stronger fibres are of little value.

Eighty percent of the farmer’s income comes from the meat and 20pc from the cashmere. Meat is becoming an increasingly attractive enterprise. However, it takes about four years for a cashmere goat to achieve the desired 100Kg live weight, to produce a 40kg dressed weight carcase for slaughter.

Whilst the dry climate (150mm annual rainfall) in western Inner Mongolia is regarded as ideal to produce the finest cashmere, to an Australian eye, the land degradation is very serious. Evidence indicates wind erosion but also water erosion resulting from the odd heavy rainfall event. It is only a matter of time I would have thought, until this issue attracts the attention of the Chinese authorities. In fact it probably already has, as farmers are now being paid 7RMB about AU$1.50 per hectare to destock.

One goat requires around four hectares. Therefore, for each goat removed the farmer receives a government payment of 28RMB or AU$7.

Apparently the average cashmere herd is around 300, with the biggest 3000. Farmers also run sheep and camels for meat production. As the land degrades supplementary feeding of corn and hay become increasingly important.

John Cordingley in the feed pen on Wulatehou farm with the eroded hills in the background. Goats and camels graze the hills during the day, returning to the feed pens in the evening. Through the yard rail can be seen a number of camels.

Inner Mongolia is bitterly cold in winter, from minus 20-30 Celsius up to minus 38-40C degrees in summer. A very harsh environment for both people and animals. Like the wool industry in Australia, the cashmere industry is under threat from competing land uses, particularly meat production. Like Australia, encroachment on land use with infrastructure for electricity grids, wind and solar farms is also evident. Poor financial returns provide farmers with little additional income to invest in farm infrastructure; – fencing, water supply to manage stock movements and herbage regeneration.

World cashmere production appears to be stable at the moment, but one cannot but wonder for how much longer farmers will continue, faced as they are with the complexities of a degrading land system, competing land uses and low financial returns.

I would like to conclude by recalling an experience I had exactly 30 years ago. On a brisk autumn day in April 1994 I had a meeting scheduled with John Sudgen, managing director of Johnsons of Elgin. Elgin is located near the mid- north coast of Scotland.

Johnstons of Elgin is the UK’s largest producer of luxury cashmere and fine woollens, using cashmere from China and Mongolia and still some lambs’ wool from Australia.

The meeting with John Sudgen was held in the Johnston’s board room. After an initial discussion, from my bag I produced a number of samples of Merino lambs’ wool – deep crimping, with beautifully aligned silky soft fibres. Wool that then for want of a better name we called elite, later trademarked, unwisely in my view, by Dr Jim Watts, as SRS.

As John Sudgen handled these samples with the skill of a master craftsman, he eyed me with a mixture of amazement and caution. Very soon he asked various members of his processing team to join us around the board room table.

Eventually he said to me: “How much of this wool is available in Australia?” I replied there was a lot, and there would soon be a lot more, because of the breeding revolution underway in Australia led by Jim Watts.

Sudgen replied: “This is a tragedy. You have arrived here two years too late! Two years ago we, together with other wool processors in the UK and Italy, agreed we were all fed up with the politics of the Australian wool industry and we decided we were going to put our money and our efforts into promoting cashmere as the world’s premier luxury natural fibre and move away from wool”.

Such is the lament of the world’s natural fibre producers.

HAVE YOUR SAY