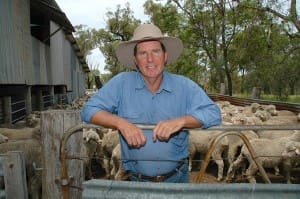

Cunnamulla livestock producer Jim McKenzie wonders why more landholders aren’t considering using electric fencing to control wild dogs.

The chairman of the National Wild Dog Action Plan steering committee thinks electric fencing gives effective control at a good price.

“Everyone seems to want to build the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and it worries me that in a lot of cases people aren’t considering electric fencing,” he said.

With growing packs of wild dogs threatening the viability of sheep production in many areas, and booming kangaroo populations preventing landholders from resting country effectively, many producers are turning to new fencing as a last resort to protect their stock and their businesses.

For many that has involved building 1.5m to 1.8m high dog and kangaroo-proof netting fences either around their boundary or around clusters of adjoining properties in collaboration with nearby producers.

At a cost of $5000 to $8000 per kilometre, according to varying reports, it is control that doesn’t come cheap.

The expense involved has prompted several leaders in the national wild dog control effort to question why more landholders aren’t considering electric fencing as a lower cost control option.

In a recent interview on dog control strategies with Beef Central, National Wild Dog Control Facilitator Greg Mifsud expressed surprise that electric fencing was not being put to greater use.

Electric fencing had proven “extremely effective” across vast distances in the rangelands of Western Australia, he said, and in “up and down” hilly country in Victoria where netting fencing was difficult to put in.

There was no reason why it would not be effective in other areas he said.

“In the Mitchell grass country of Queensland for example where it is flat as a tack it would be ideal,” he said. “Run a grader line alongside an existing fence and put in outriggers, to me it makes a lot of sense.”

Mr Mifsud said he believes a lot of producers “got burnt” – figuratively, if not literally – in the past by earlier-generation electric fencing systems that may have lacked the capacity to provide effective power across large distances, and which were time-consuming to monitor and maintain.

However, he said the technology had come a long way, with new generation systems able to deliver traffic-stopping voltage over vast distances from both mains and solar-powered sources.

The checking requirement had also been made much easier in recent years by the release of automated monitoring technology.

Fence zone monitoring systems can now remotely isolate the source of a breakdown to a particular section of a fence and send an alarm back to the controller.

“That is huge,” Mr Mifsud said.

“From going along with a volt meter every 100 metres trying to work out where it has gone down, to being able to break the fence into cells and know which cell a breakdown is, the monitoring issue has improved out of sight.”

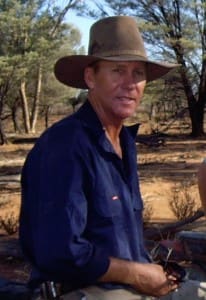

‘Electric fencing only reason I’m still in sheep’: NFF president

NFF president Brent Finlay at home on his Traprock district property Cooinda. Picture courtesy of Col Jackson, Blue’s Country Magazine.

National Farmers Federation president and former National Wild Dog Management Advisory Council chair Brent Finlay is another advocate for electric fencing after putting the technology to effective use in recent years on his Traprock district property Cooinda.

After “getting smashed” by wild dogs and losing 600 sheep four years ago, Mr Finlay and his neighbours ran a simple electric fencing configuration to control dogs along their existing boundary fences, which comprise mainly old rabbit-proof netting.

In his own case on Cooinda, Mr Finlay ran an offset plain earth wire about 100 millimetres above the ground with an offset electric wire 150-200mm above that. The wires are offset on the inside of the netting boundary, positioned to belt back any animal that tries to push through holes in the old rabbit netting.

Combined with vigilant and coordinated baiting and trapping programs that target known dog corridors, Mr Finlay said the electric fence has been a big success on Cooinda.

Only once have wild dogs entered the property in the four years since the fencing was introduced. That incursion occurred last Easter when a fallen tree caused a breakdown in one section of the fence. Four dogs crossed into Cooinda while the fence was down. The dogs were soon picked up via traps and baits inside the property.

Mr Finlay, whose fence was built before the introduction of automated zoning technology, said it took about four hours a week to check and maintain the 20km of electric fencing around Cooinda.

“It takes a bit of time, but the benefit is that without it we would have had to have gone out of sheep,” he said.

Electric fencing had enabled him to do a lot of fencing to protect his property very quickly, he said.

“If you can afford to put up a new dog proof netting fence that is fantastic, but for a quick fence that works, electricity is a good way to put up a lot of kilometres and to take the pressure off your business,” he said.

“Given the outlook for red meat and red meat protein, it is so exciting whether it is sheep or cattle, and they’re worth a lot more now and anything you can do to prevent those losses is money in your pocket.”

Front line defence in Victoria

Electric fencing is being far more readily embraced as a dog control measure by producers in southern areas such as Victoria, where many landholders have already “fenced themselves in” against the dog threat, according to Barry Davies from the Victorian Government’s Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning Wild Dog Program.

Electric fencing has “definitely been effective” in the State, Mr Davies said, and was the only reason many producers had been able to stay in sheep production.

Mr Davies, a former manager of Western Australia’s wild dog control program and a founding member of the National Wild Dog Management Advisory Council, said the Victorian Government is actively promoting the use of electric fencing as a front line defence against wild dogs.

He cited the experience of one landholder in the Tallangatta Valley who recently invested $8000 to run a single offset electric wire around his 6km ringlock boundary fence after wild dogs caused severe losses during lambing.

In his first lambing after installing the hot wire, Mr Davies said the resulting increase in lambing percentages effectively reimbursed the full $8000 cost of the fence to the landholder, “plus an extra 25pc on top of that”.

10 year success with electric fencing at Cunnamulla

At Cunnamulla in South West Queensland, Jim and Trish McKenzie began using offset electric wires inside their paddock fences to keep goats in about 10 years ago.

Now with the wild dog threat and kangaroo pressure growing, the McKenzies are adding offset electric wires to the outside of their boundary fence in a bid to keep dogs and kangaroos out.

Several properties in their area are building netting fences for the same purpose, assisted in many cases by subsidies of around $2000/km from the local Natural Resource Management (NRM) group.

Mr McKenzie said electric fencing has worked effectively for more than 10 years on Gamarren Station and he believes other nearby landholders could achieve the control outcomes they are seeking for a lower cost by using electricity instead of netting.

The strategy the McKenzies have found most successful on Gamarren is to run an offset hot wire on each side of their plain wire fences, positioned with poly droppers about 250mm from the fence and 250mm off the ground.

Ther 30km of hot wires now in place were effectively stopping both dog and kangaroo traffic, Mr McKenzie said.

He said that while many landholders expressed concern about the monitoring and maintenance requirement of electric fencing, the new remote zone-based monitoring technology was “a big plus”.

“It is easy to look at the board and see which part of the fence is not working and then go straight to the problem,” he said.

“You can also get it on your 3G (mobile phone) and you can monitor your fence wherever you are.”

“We think that with the electric fencing we are doing now, and talking to Gallagher and other people about it, we think we get good control without having to spend $5000 to $8000 a kilometre to achieve that.”

Mr McKenzie said one issue preventing a greater uptake of electric fencing was the tendency of groups managing cluster fencing programs to act like a “body corporate” and determine the type of fencing that must be used.

“If I want electric fencing and I am voted out, I have got to go to 1.5 or 1.8m high exclusion fencing, there is no in between. I think it should be included, people have to make their own choice.”

Mr McKenzie said each landholder in a fencing cluster was required to check and maintain their section of the fence. “It is no different to keeping an electric fencing operating.”

All of the dog control experts Beef Central spoke to about exclusion fencing stressed the need for continued coordinated control methods such as trapping, baiting and shooting focusing on known dog corridors.

For further information and case studies documenting other landholder experiences with electric fencing for wild dog and kangaroo control, visit Beef Central’s Wild Dog and Pest Control page – click here

I used to be an advocate for Electric fences for my Meat Sheep clients, many of whom have embarked on 1.5m with skirted Feral fences for distances from 40km to 140 km to surround just one property. One client is about to embark on a 220km boundary at an estimated $6000/km including labour, materials, dismantling and clearing costs. Their rationale seems to be a high cash flow Meat Sheep enterprise, the massive lift in lamb markings and survival can quickly pay off the investment. Also, Banks recognize there is an upward revaluation of the property; their maintenance time is much lower; pigs and roos are now controllable as well as dogs with a possible 30% lift in stocking rates or spelled country. The lifetime of a new fence of 50 years is estimated (with non Chinese materials). Most properties are in open Qld Mitchell grass downs country with little scrub and flatter topography than Brett Finlay in the Traprock and fewer trees than Gamerran. They do have expensive end sections and creek crossings to negotiate in self mulching black soil that jacks posts out of the ground over time. Only one client on the Maranoa (red soil) has elected to go electric and that only on internal fences of conventional design and construction with 5 plain wires highly tensioned. His 45km boundary is 1.2m high, without skirt, and of tight mesh topped with 2 barbs. The decision becomes easier for cluster merino properties where a high Feral fence is preferred because not all members have a boundary with the fence and fence costs cf individual property fencing is very low, possibly lower than the Gamerran Electric job (See Morven, Tambo, Barcaldine and Blackall clusters already up or under construction enclosing well over 100 properties.) Their maintenance and construction costs are comparatively low and they have a new fence in most cases (except Morven), instead of a renovated fence. Their decision seems much easier, so long as they have strategies for fence maintenance, as well as the control and exclusion of Feral animals. The promise of complete exclusion rather than vigilance and maintenance, as well as favourable depreciation costs may be what tips individuals into mesh fences Jim? I admit this would be a more vexed question for merino Producers with lower cash flows. But both the Blackall and Tambo and soon the Barcaldine clusters will enclose low cash flow cattlemen who have no intention of returning to sheep, who see a property revaluation advantage, in being members of a cluster. I foresee more will follow, unconvinced of the virtues of electric fencing even with remote zone fault detection technology, to cover very large distances of exclusion fencing. Especially where few may be seen to be responsible to maintain the fence. I do, however, see a place for internal and isolating electric fences or offsets during the feral clean up stage of eradication, being very useful.