National Wild Dog Management Plan coordinator Greg Mifsud

AUSTRALIA’S national wild dog management coordinator has suggested recent research and control measures fostering healthy populations on public land indicate the dingo no longer qualifies as a threatened species in Victoria.

As the Victorian Government reviews the future of the state’s wild dog program, National Wild Dog Management Plan coordinator Greg Mifsud has suggested current control measures are maintaining a sustainable self-replacing population of dingoes on the state’s upper north-east and north-west public lands.

The Victorian Farmers Federation has urged the Victorian Government to renew the state’s wild dog program, arguing that baiting and trapping in a three-kilometre livestock protection buffer around public lands has delivered genuine conservation outcomes and reduced wild dog attacks on livestock in the past 11 years.

Victoria’s Wildlife Act (1975) Order In Council ‘unprotects’ the dingo on private land, and on public land within 3km of the private land boundaries to public lands. Recommendations in the Parliamentary Report into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria include removing the Order In Council with its three-kilometre livestock protection buffer, reintroducing dingoes in some parks and phasing out 1080 baiting. There are concerns this could lead to dingoes being protected as a threatened species on private property as well.

The Order in Council is due for renewal on October 1, 2023, but Mr Mifsud said if it is not renewed all wild dog management activities on public land will cease.

Earlier this month, the Victoria Government told Sheep Central it is carefully considering the Parliamentary Report into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria and its recommendations, and will issue a response in due course.

Earlier this month, the Victoria Government told Sheep Central it is carefully considering the Parliamentary Report into Ecosystem Decline in Victoria and its recommendations, and will issue a response in due course.

“We will continue to work with Traditional Owners, farmers and private landholders to appropriately balance the protection of livestock and dingo conservation,” a spokesperson said.

Through existing programs and regulations, the Victorian Government said it is supporting farmers to apply best practice management of livestock predation. This included the targeted deployment of some or all lethal and non-lethal control techniques such as fencing, baiting and the use of guardian animals. In combination with other control measures, 1080 continues to be used for protecting Victoria’s biodiversity and livestock industries from pest animals, the government said.

Ministerial letter puts the case to continue wild dog control

In late July this year, Mr Mifsud wrote to Victoria’s Minister for Environment Ingrid Stitt and Minister for Agriculture Gayle Tierney stating that the Victorian Wild Dog Management Program has reduced wild dog impacts on livestock and domestic pets on adjoining properties and limited their spread into other areas.

“All of this has been achieved without destabilising dingo populations on public lands, bringing into question the need for dingoes to remain listed as protected in Victoria under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.

“Further, the success of this approach and current genetic data from current research would mean that recommendations 8 and 28 of the Parliamentary inquiry into Ecosystem decline in Victoria, are no longer relevant, as the dingo and its populations are neither in decline nor threatened by control programs delivered in the in the 3km Livestock Protection Buffer (LPB) under the Order in Council made under the Wildlife Act 1975,” he said.

Mr Mifsud argued that an additional benefit to the implementation of the protection buffer is the protection of the genetic integrity of the Victoria dingo population.

“The genetic integrity of dingo populations is threatened by hybridisation with domestic dogs (wild or owned).

“Recently published research on the genetic composition of dingoes across Australia (by UNSW Australia research fellow – canid and wildlife genetics Dr Kylie Cairns) indicates wild dog management delivered in the 3 km LPB has contributed to significant improvements in the purity of dingoes on public lands in eastern and north-western Victoria,” he said.

“The genetic analysis Cairns et al (2023) shows the genetic purity of dingoes within conservation areas in Victoria has increased from 4pc in 2015 to 84pc currently.

“This increase in genetic purity of dingoes within Victoria temporally coincides with the implementation of the 3km LPB, and the associated increase in wild dog control by the Victorian Wild Dog Program from 2010 onwards.”

Mr Mifsud believed the increase in dingo genetic integrity identified by Dr Cairns is among the potential benefits to dingo conservation generated by the Victorian Wild Dog Program, along with preventing or limiting crossbreeding with domestic dogs, while protecting livestock and domestic pets.

“In addition to targeted ground and aerial baiting, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) wild dog program staff have, on average, trapped 550 to 600 wild dogs/dingoes each year for the past 10 years in the public-private land interface, with no downward trend evident in these numbers.

“At face value this may seem like a Sisyphean task; however, these results are positive from a dingo population perspective in that they indicate that the dingo population on public land within the LPB is stable, self-replacing and not showing a downward population trajectory,” he said.

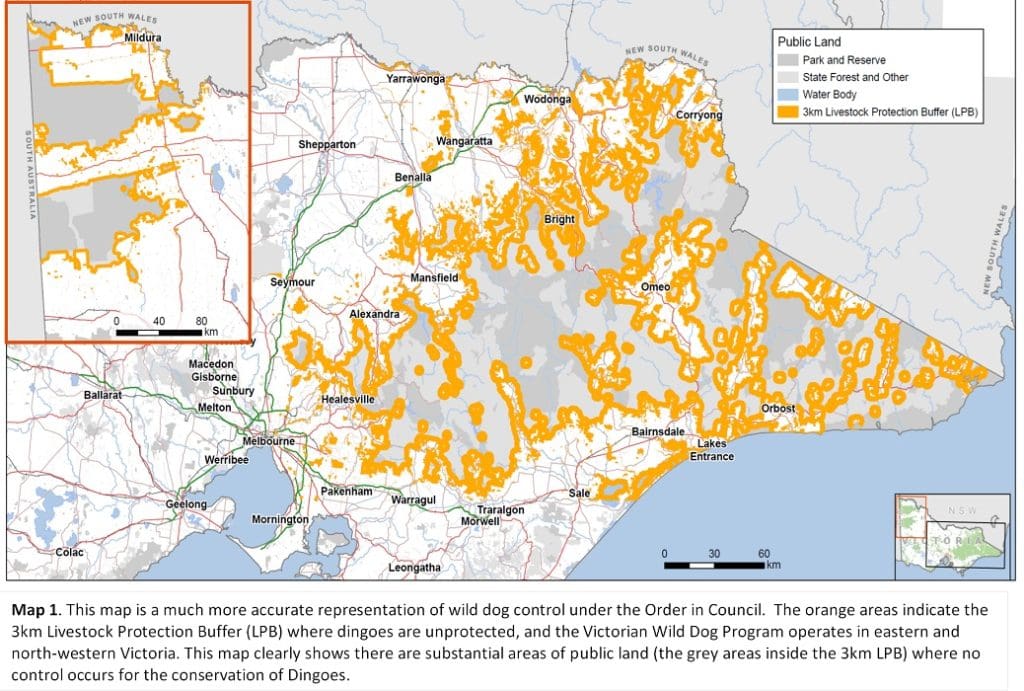

“Critically, the DEECA Wild Dog Program is only conducted on approximately 1.60 million ha of the 4.7 million hectares of public lands in the east and north-west of the state.

“This provides over 3.1 million hectares of public lands including, state forest, and national park where dingoes can reside undisturbed,” he said.

“The areas in the north-west of that state clearly illustrates that the 3km LPB is a very narrow strip compared to the huge landmass of the Big Desert and Wyperfield National Parks, with control only delivered in areas to the east where historical and ongoing attacks on livestock occur and certainly doesn’t threatened the existence of the population, as has been suggested in recent media.”

Mr Mifsud said wild dog control conducted in the protection buffer is highly strategic and targeted in nature and the area under control is significantly less than the 1.6 million ha that the LPB occupies. The DEECA wild dog management work zone maps show clearly the targeted nature of the control activities and the fact that there are significant areas within the LPB where management does not occur, he said.

Dingo’s threatened species status queried

Mr Mifsud said available dingo genetic research and population data indicates that the dingo does not qualify as a threatened species under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 under the criteria listed in Section 11 of the Act.

Under Section 11 (1) of the Act, a taxon or community of flora or fauna is eligible to be listed if it is in a demonstrable state of decline that is likely to result in extinction or if it is significantly prone to future threats that are likely to result in extinction.

Mr Mifsud said it has been established that the dingo is not a separate species, and is taxonomically not different to a domestic dog, hence the scientific name Canis familiaris. He said recent DNA research suggests all wild living dogs on Victorian public land in eastern and north-western Victoria meet the criteria to be considered dingoes, according to Dr Cairns et al (2023).

“The DEWLP Victorian Wild Dog Program figures indicate that there is a consistent number of dingoes removed from the LPB annually since 2010 indicating a sustainable, self-replacing population of dingoes in the public estate.

“Estimates based on published home range sizes indicate that dingo populations within eastern and north-western Victorian can be considered abundant,” he said.

The Act also stipulates that a taxon of flora or fauna “which is below the level of sub-species and a community of flora or fauna which is narrowly defined because of its taxonomic composition, environmental conditions or geography” is only eligible for listing as threatened if in addition to the requirements of sub-section (1) there is a special need to conserve it.

Mr Mifsud said the dingo is widely distributed and abundant across its range in Victoria.

“Conservative estimates provided here put the population at over 5000 individuals.

“Its habitat and distribution on the public lands on which it exists are not under threat and are not likely to contract in the near future.”

Keeping the 3km buffer will keep pure dingoes on public lands

Mr Mifsud said keeping the 3km Livestock Protection Buffer will ensure protection of high purity dingoes on public estate while limiting the impacts of dingoes on livestock production, domestic pets and human health should they be allowed to spread into new areas of the state.

“The renewal of the Order in Council and maintaining the 3 km livestock protection buffer is paramount to achieving ongoing conservation and pest management objectives and outcomes for those living in and around the public lands where dingoes persist and for the broader Victorian public who wish to see dingoes protected on National Park and public lands within Victoria.”

‘Killing dingoes does not help conserve dingoes’ argues researcher

Dr Kylie Cairns

Dr Cairns said a letter by 25 scientists and researchers from around Australia has been sent to the Victorian Government about the need to revise current public policy in Victoria, including revoking the current Order in Council that unprotects dingoes (a threatened species) within 3km buffer zones.

She did not accept that wild dog managements plans had played a role in maintaining genetically pure dingo populations on public lands and suggested Mr Mifsud had misunderstood or misinterpreted her recently published research.

“There is no evidence that current wild dog management plans have benefited dingo populations on public lands in Australia.

“Rather, there is evidence that dingoes rarely interbreed with domestic dogs and have maintained their genetic identity despite ongoing persecution and the high density of domestic dogs (as pets) in Victoria,” she said.

Nor did Dr Cairns believe that the Victorian Wild Dog Program has limited crossbreeding between dingoes and domestic dogs.

“Killing dingoes does not help conserve dingoes.

“We have observed in our new DNA studies that dingo x dog hybridisation is most common (although still rare) in regions with long term intensive lethal control programs and a high density of pet domestic dogs,” she said.

“The single study completed in Australia on this topic was unfortunately carried out in a region with a low domestic dog population and only sporadic lethal control so it is not informative to this issue, particularly in Victoria.

“We can see from published genetic data that dog ancestry is more common in regions with intensive lethal control (aerial baiting) and higher densities of pet dogs.”

Dr Cairns said there is no reliable census or survey data across Victoria that would allow an assessment on whether the annual number of dingoes killed in public lands is sustainable or to assess the current vs past population size of dingoes across the state.

“Additionally, this does not consider the genetic impact of regularly removing dingoes from the breeding population, which may lead to inbreeding and genetic bottlenecks.

“Consistent removal of a certain number of dingoes from the environment does not provide any evidence about the health, abundance or density of dingoes in Victoria and cannot be used as evidence that the dingo population is healthy or self-replacing,” she said.

“Baseline census data would be needed to assess whether the current ‘take’ of dingoes from public lands is sustainable, and more detailed genomic data would be needed to assess if this ‘take’ is having an impact on the genetic health of dingoes.”

Dr Cairns said there is no evidence from DNA studies in Victoria to suggest that killing dingoes in the 3km public land boundary zone provides benefit to dingoes, and there is insufficient data available to properly assess the health of dingo populations in Victoria.

“The preliminary evidence we have would suggest that there concerns around the ongoing genetic viability of some dingo populations with the observation of low genetic diversity and high homozygosity.

“Furthermore, the fragmented nature of conservation reserves in Victoria (and elsewhere) may be limiting geneflow between dingo populations,” she said.

“Whilst genetic data shows dingo populations in Victoria have remained genetically intact, this does not mean that dingo populations are healthy, more research is needed.”

Dr Cairns does not think there is currently adequate data on the genetic health, population size, range or the threats experienced by dingoes to revise the Threatened Species Listing at this time, “and any review must be based on rigorous scientific data by the Victorian Threatened Species Scientific Committee, not by the Co-ordinator for the National Wild Dog Action Plan.”

She said a preliminary study published today has suggested that dingoes across Australia carry low levels of genomic diversity as a result of evolutionary bottlenecking.

“This low baseline genomic diversity may make dingo populations more vulnerable to genetic declines following lethal control programs, like the program continuing in Victoria. See Kumar et al. 2023 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ece3.10525”

Dr Cairns said the genomic data in her crossbreeding or dingo-domestic dog ‘admixture’ research indicated that dingoes in Victoria have not ever been compromised by domestic dog introgression, not that dingo ‘purity’ has increased.

“In fact we show that previous methods of DNA testing used by Centre for Invasive Species Solutions, State Governments and researchers are biased and misidentify pure dingoes as hybrids.”

The research found that in Victoria, where previous reports suggested the pure dingo population was as small as 4 percent, the study found 87.1pc of animals tested were pure dingoes and 6.5pc were historical dingo backcrosses with more than 93pc dingo ancestry. In New South Wales and Queensland, where dingo-dog hybridisation is assumed to be pervasive, most animals were found to be pure dingoes, and only two wild canids had less than 70pc dingo ancestry. Little evidence of hybridisation in the dingo population was also found in the Northern Territory, South Australia, and Western Australia.

Dr Cairns reiterated that her research does not show that the genetic purity of dingoes increased from 4pc to 85pc.

“It shows that previous research (which reported 4pc pure dingoes remaining) was incorrect, because it misidentified pure dingoes as hybrids.

“Further, there is absolutely no evidence that there was a change in dingo purity coinciding with the implementation of the 3km LPB.”

Dr Cairns said in Victoria, dingoes are listed as Canis lupus dingo, but the IUCN SSC Canid Specialist Group she is a member of will be undertaking a review of the taxonomy of all canids, including dingoes. She noted that dingo taxonomy is hotly contested with names used including Canis familiaris, Canis dingo and Canis lupus dingo.

“The recent observation of reproductive isolation (ie little interbreeding) between dingoes and dogs, as shown in my published scientific study, along with other lines of genetic and morphological evidence, suggests that the dingoes are distinct from dogs.”

Neither Minister for Environment Ingrid Stitt nor Minister for Agriculture Gayle Tierney would comment this week on whether the Victorian Government was considering changing the Threatened Species status of the dingo in Victoria. Instead a Victorian Government spokesperson reiterated:

“We will continue to work with Traditional Owners, farmers and private landholders to appropriately balance the protection of livestock and dingo conservation.”

In support of Mr Mifsud’s comments, dingoes have been baited, shot, excluded, frightened off and called names ever since Europeans tried running sheep and cattle in Australia. Yet despite this there is still a very healthy and self-replacing population that by its existence provides the ecological high order predator service lauded by some ecologists. On the other hand, sheep and cattle producers have a degree of protection that would not be afforded by a no-control situation.

The current Victorian Government approach through the 3 km livestock protection buffer is a working compromise to meet both concerns and should be continued.

Furthermore, the social justice ramifications alone of allowing dingo numbers to reach their natural population level adjacent to farm businesses and recreational areas would be significant and politically problematic.

Firstly I would like to thank the Victorian Government for the work that is being carried out to protect livestock

As producers in the Victorian high country, we face the constant threat of wild dog attack. The work that is involved to protect our livestock is enhanced by the control programs carried out in the 3km buffer zone. I find it very offensive to be labeled lazy. We have invested heavily and worked hard to protect our livestock.

It’s interesting that people with nothing to lose have the most to say. We all like to go to bed at night to rest knowing what we are working for is safe. This is an integrated approach that needs every tool in the tool bag.

Thank you for your consideration,

Simon and Sonya Lawlor, Omeo

It is important that the Victorian government understands that the use of 1080 baits and other lethal measures for controlling wild dogs and foxes usually form part of an integrated pest management strategy for most small livestock producers. The preservation of the dingo breed must be balanced by the rights of farmers to protect their stock from what can be quite vicious attacks. This is not an academic argument for farmers, but a lived reality that affects not only their ability to earn a living, but also their psychological well being. Most farmers care about their livestock and suffer emotionally when they are attacked. Perhaps that also would be a worthy topic of academic research?

As to the semantics surrounding the naming of dingoes, two points are relevant. If they can interbred with domestic dogs, then they meet the biological definition of a single species. Livestock farmers might actually know a thing or two about breeding by the way. The other important point is that dingoes aren’t native to Australia. They arrived in Australia around 3500 years ago, or shortly before that time. Victorian farmers are therefore being asked to wear the direct cost of preserving a breed of introduced wild dog (or possibly a sub-species if you prefer) to satisfy the calls of largely urban-based academics.

In conclusion, if purebred dingoes stay more than 3 km away from private farmland in state forests or state and national parks, they are under no threat. My conversations with those trapping wild dogs in north-east Victoria suggest numbers are healthy. I know that’s not a scientific survey, but people living near or working in the bush usually have a few clues as to what’s going on in the environment around them. If more detailed surveys are required, why not conduct them before removing the tools that we know work at reducing wild dog attacks? Clearly those that seek to protect wild dogs care more about them than they do for the livestock they kill and the farmers that are affected by their brutal deaths.

Calling our farming techniques lazy and cruel is an unbelievable statement. Clearly made by someone who has never spent time on a farm. Farmers that we know show incredible care for their animals.

We have lost 30 lambs and two ewes over the last two months in nine separate attacks. The dogs come under cover of darkness and fog and terrorise the sheep. They slaughter at will and leave stock dead or severely damaged in their wake. This is despite having guardian animals, flashing lights and live fencing. We also had several ewes aborting their lambs during the terror of the attacks.

We did not feel lazy building many kilometres of extra fencing and carrying away dead lambs and/or shooting those that were left alive and suffering for many hours during the night.

We do not feel lazy when we check our animals morning, noon and night to ensure they are all ok.

We cannot walk through the bush for fear of encountering packs of dogs/dingoes. We need some help from our neighbours, the Government. We must keep the 3km buffer and keep the wild dog management teams in place.

Dr Kylie Cairns is pictured holding a gorgeous dingo pup, and not so gorgeous when these 12 month-old pups are fighting over and tearing apart other young wallabies, kangaroos, possums, spiny ant eaters and the many other native animals that share and inhabit our gorgeous natural bushland. They are carnivores and therefore only survive on either native animals or farmed animals. If left unchecked many more native animals will suffer. Producers take many measures to keep dingoes out of farmland to protect their animals that include electric fencing; however, restrictions on tree clearing on boundaries along side state forests means there are always issues with trees falling over fences, wombats pushing through etc. We need a commonsense approach and the department has been working hard to keep our animals safe please,. Do not make it any harder for them.

Greg Mifsud has worked tirelessly as the national wild dog facilitator for well over the last 15 years and during that time has worked alongside many of the leading wild dog/dingo researchers in Australia. These researchers have provided objective insight into the many facets of wild dog/dingo existence as well as the many species that they impact upon. In Greg’s role he has worked with farmers and the various state departments to achieve sustainable wild dog control methods that follow best practice. He was also responsible through the National Wild Dog Action Plan for obtaining the funding for the Guardian Dog Best Practice Manual.

As a sheep and beef producer in north-east Victoria, I need peace of mind that my livestock will not be impacted by wild dogs. Guardian animals are limited in their effectiveness and I have to rely on the proven effectiveness of traps and baits. It’s disheartening when confronted with the mindset that it’s all about the total eradication of the dingo when this has never been the objective.

Firstly I must object to the comment that farmers are lazy. Where is the evidence? It seems to me that Victoria’s 3 km buffer zone adjacent to national parks has worked well in protecting livestock production, while ensuring native wildlife sustainability within the parks. If the system isn’t broken, why break it?

Everything, including nature, must work in balance. The 3km buffer zone provides just that. Dingoes/wild dogs have thousands of square kilometres to roam, unimpeded. The Government and private landholders presently carry out sporadic, but highly targeted control measures in a tiny portion of that. As beef producers in the heartland of wild dog country, we see first hand their impacts. Their presence ebbs and flows with the seasons; however, when their numbers increase, our kangaroos, wallabies and lyre birds disappear. Nature’s balance is set awry. The dingo has only been in Australia for 5000-odd years, the rest of our native animals have been here for millennia. They were not designed to outwit their stealth, cunning and speed. It makes sense to have zones where dingoes’ impacts are at least moderated – giving our other native animals a fighting chance.

From a producer’s point of view, my sympathies are with our cows, on constant guard during calving season, which always brings in the dogs/dingoes. Cows are highly sentient beings, they know grief and it’s more pain than most of us can bear to have animals watch their offspring torn to pieces and eaten alive, despite anything they do to save them, and they do try. It’s easy for the nay-sayers to label farmers as ‘lazy’, ‘backward’ and the like. It’s easy to make sweeping decisions from ivory towers. Come down here at ground level, see what they really do. Watch it. Feel it. And then tell me we don’t need some sort of balance.

A transparent inquiry into the dingo killing industry is required to separate myths from fact. There is too much conflict surrounding issues that academia cannot agree on. Having stock producers base their arguments on what seems to be misinformation provided to them by an organisation set-up and run by agricultural groups and poison maker ACTA is a sad and sorry situation.

I am from a farm, and have worked across Western Australia from Halls Creek to Esperance since the mid 90s in shearing teams, stock camps, fencing, and now as a prospector. I can see that the wild dog problem in WA where I have lived and worked at least is not as prevalent as CISS, NWDAP, some pastoralists, ACTA and government departments want people to believe. Dingo management is not as simple as kill, kill, kill. They need to have their pack stability to function properly to protect vulnerable species against invasive predators, and to combat overgrazing from native and invasive herbivores. I appreciate that stock need to be kept safe from predation; however, causing native extinctions as a result is not an acceptable option.

If dingoes were a problem in WA during the 90s then I never heard or saw evidence of it. What I really find problematic is that ACTA appears to still have a major interest in CISS, thus influencing the amount of 1080 we buy from him and pollute our bush with. It would be in the best interest of all parties to scrap the current arrangement and start again with input from all credible sources. From where I stand, CISS and ACTA are taking Australia for a ride, using stock producers as the scapegoats and that’s not to mention the disgraceful conduct of the APVMA with Barnaby at the helm, for the current and impending native species extinctions brought about by removing our only Apex predator, and allowing the spread and establishment of foxes, cats and rabbits. The only winner will be ACTA who will be selling 1080 to us for another 50 years.

I feel quite strongly that this is ACTA’s long-term plan as discussed by Linton Staples in 2004 in his submission to the parliamentary inquiry into pest animals. As an advocate for both, my beloved pastoral Industry and our majestic dingoes, I believe we can manage this situation much better, and we owe it to future generations of Aussies to sort it out now.

Thank you for this opportunity to speak up.

Mr Misfud is making statements without any evidence or knowledge. I strongly urge the Victorian Government to stop the baiting — poisoned meat all over public lands that kills everything it comes into contact with — and trapping. I would be interested in seeing how many Australians other than ranchers feel the “wild dog” management program needs overhauled. Dingoes are not dogs.

If Australian farmers want to protect their livestock then they need to be responsible and use guardian animals like donkeys or LED’S and stop using 1080.

Nobody has every disputed the farmers right to protect their livestock. It’s the government condoning the use of 1080 that is the biggest concern. Our farming techniques are lazy and cruel.

You will always gets issues when people with potential vested interests get involved. Mr Mifsud and some of his colleagues have a proven history of negativity towards dingoes and coming up with “research” which is in total opposition to that from the majority of peer reviewed science. When one’s job consists of peddling 1080 poison and killing dingoes for a living, questions must be asked as to the true motive, his words must be interpreted in that context.

At the end of the day, people like dingoes and the sheep industry needs to learn to coexist with them. A position of balance is needed to ensure the survival of dingoes and also that of the sheep industry.