MAJOR flaws exist in the AusVetPlan’s approach to compensation for stock losses associated with any outbreak of Foot & Mouth Disease in Australia, independent analyst Simon Quilty told an industry gathering on the Gold Coast yesterday.

Speaking during the Rural Marketing Agents (RMA Network) annual conference, Mr Quilty painted an alarming picture about the financial impact on livestock producers of an FMD incursion from Indonesia. He exposed what he sees as serious flaws in the size of the available compensation package for stock liquidated in the disease response, and the methodology used to compensate producers for lost stock.

Simon Quilty, addressing yesterday’s RMA Network conference on the Gold Coast

As background, the current AusVetPlan document (Click here to access) sets out circumstances that would unfold in the event of an FMD outbreak*. All animals would be slaughtered on premises where an infection had been detected, and any animals in ‘suspected’ herds would be observed closely for 14 days.

There were effectively three parts to the government’s compensation process, Mr Quilty said.

The first was animals lost immediately in the eradication process. The second was response costs including decontamination (ie a shed where infected animals had been found, being burned down). The third was compensation for those producers who had been forced to destock, who then had to go into the market re-stock. Effectively, the government would pay the difference if the cost of the new stock was higher than at the time of destocking. (36.30)

Compensation is determined by the states and territories, but under the Australian Emergency Animal Disease Response Agreement, the state and federal governments would share 80pc of response costs, with the industry paying the remaining 20pc.

Mr Quilty firstly set out a series of major concerns about how the compensation process would unfold.

In a herd or flock where the disease was found, under the agreement, the value of animals would be determined by the prices at the two most recent sales that had taken place at the closest saleyards to the affected property.

“But under an FMD crisis, the impact is a rolling problem. In a week’s time, the livestock sales continue, but the market is shut off, and prices plummet. In a herd that contracts FMD a week later, their compensation is determined by the local saleyards prices that week.”

“If in three weeks’ time the market has crashed 50pc, the same happens again – it’s a rolling compensation. Effectively, producers are going to wear the cost of market closures, so you do not want to be the last to contract FMD in your herd – you’d better be the first, because only the first will get pre-FMD prices for compensation. At the other end, the last guy whose suffers a herd infection gets the worst prices ever,” Mr Quilty said.

“It’s wrong. It should not be that way, and represents policy poorly written. In my opinion compensation should be based on a set time period prior to any FMD outbreak – not some ‘rolling average’ of prices once the disease strikes.

Mr Quilty urged RMA members attending yesterday’s conference to take the messages home to their local politicians, and seek to ‘get it set right.’

“It’s a major flaw in the AusVetPlan. And who’s going to suffer? Livestock producers and others along the red meat supply chain.”

Void in data collection

Concerns also arose over categories of cattle and sheep – grainfed animals, grassfed animals, different stages on feed, and the markets for which they were destined.

“The problem is, MLA stopped reporting months ago on some of these categories,” Mr Quilty said.

“For example the Eastern States paddock feeder steer indicator has not been reported since March 19, 2021. Similarly, grainfed cattle indicators for 70 and 100 day cattle ceased on 13 December last year*. (*editor’s note: Beef Central inquired about some of MLA’s paddock market indicator cancellations when they occurred. We were told it was driven by a lack of cooperation from stakeholder participants in routinely delivering prices, making quotes unreliable).

“MLA has pulled back dramatically on a lot of its price reporting – and most of it is at the quality end of the market,” Mr Quilty said. “How can you determine the value of a high-end grainfed animal, for example, when the data does not exist?”

He said for the purposes of compensation, ‘beef cattle’ were divided into three categories: regular livestock, grainfed, and stud cattle. Sheep also had separate categories.

Non-insured stud cattle (ie breed society registered), would receive a 25pc premium for heifer calves in the event of liquidation and compensation, cows 50pc, bull calves 200pc and bulls at a 400pc premium.

“But for a lot of people, this may still be truly undervalued, even based on pre-FMD pricing, and the same holds for stud sheep,” Mr Quilty said.

Simon Quilty speaks to one of his slides during yesterday’s RMA conference presentation

Stop all sales

“Everything is concerning to me. If I was in a beef or sheep producers’ shoes, under these arrangements, I would want to simply stop all sales everywhere, in the event of an FMD outbreak.

“You may as well stop all livestock sales as soon as FMD hits Australia – that way everyone in the room is guaranteed a pre-FMD livestock price compensation package.”

Mr Quilty said the quality end of the cattle market would hurt the most under an FMD outbreak, and subsequent export market closures.

“Take Wagyu and Angus fed cattle and feeder cattle for example. I think we would be in all sorts of trouble trying to put a value on those animals in the event of a disease incursion. Now is the time to get it right.”

Is the livestock compensation fund a bottomless pit?

Mr Quilty also explored the compensation fund’s (financial) ability to cope with mass liquidation of cattle and sheep in the event of an outbreak.

“Is the compensation fund a bottomless pit?” he asked.

He said under Commonwealth legislation, there was an ‘agreed limit’ on compensation of 2pc of the gross value of production of the industries involved, before both states and federal governments would consider committing any more resources.

ABARES’ recent estimate of Australia’s meat and livestock sectors’ gross production value was A$36 billion. It means that the agreed limit given to the industry under these terms would be $700 million.

Over the past 30 years, a sliding scale had been devised by government when estimating the cost of livestock compensation and control costs. This was based on the size of the outbreak and the time period to bring it under control.

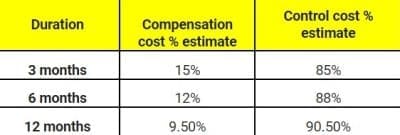

Based on this data from AusVetPlan, Mr Quilty provided some estimates, as a guide, of how the disease management costs would be distributed (see table below).

“Effectively, anywhere from 9.5pc to 15pc (depending on the duration of the problem) goes towards compensation for cattle losses. The other 85-90pc goes towards disease control measures,” he said.

“Effectively, anywhere from 9.5pc to 15pc (depending on the duration of the problem) goes towards compensation for cattle losses. The other 85-90pc goes towards disease control measures,” he said.

“You would think it would be the reverse, but it’s not – the cost of control, of setting up zones, disposing of animals and everything else involved in the response, is anywhere from 85pc to 90pc of the total cost.”

Mr Quilty said this meant that there was somewhere between $66 million and $105 million to pay for cattle compensation to producers, and for broader disease control costs, around $595m to $635m.

Based on a commercial beef animal worth $2500, that meant there was enough money to provide compensation for only 26,000 to 42,000 head of liquidated cattle.

“To put it into sheep terms, the compensation fund would cover only 373,000 to 600,000 head. But that’s not for both sheep and cattle. It’s one, or the other, in terms of that compensation example.”

“That’s it. That’s the number. Remember that in the UK’s FMD episode, they killed seven million head.”

“I think they are sobering numbers. It’s not to say that the money stops there, but it shows us just how much is in the till – and it ain’t much. In reality, at $700 million (total compensation package), the government would have to coming back and dishing out more money, as need be. So the point of the review is the clear message.”

Domestic market impact

If it took three months to get to ‘stage four’(eg outbreak stabilised and under control) in the AusVetPlan’s post FMD outbreak management plan, it would mean the domestic market would stop for three months, because no animals would be slaughtered, due to the poor policy surrounding compensation.

“That would cause enormous problems, because 50pc of the Australian domestic beef market relies on fresh (chilled) beef trade, not frozen,” Mr Quilty said.

“We could not use the frozen beef that could be in the pipeline, coming back from export customers who had rejected it due to the outbreak, because the industry simply is not geared up to handle it. It creates a big problem – the domestic meat market cannot function, and suddenly the shelves are bare.”

Mr Quilty said as part of his meat trading business, he had spoken to a New Zealand processor this week who had told him he had started to get calls from large Australian red meat end-users over possible supply, in the event of an FMD outbreak in Australia.

“Everyone in the food industry is now getting truly concerned about the wheels of business stopping, because of poor policy,” he said.

“To think that under an FMD detection, we’d have a glut of cattle that can’t go export, and yet we’re going to slow down our domestic market so much that they are already exploring prospects for NZ beef to come in here. Go figure.”

“Are you understanding the magnitude of the problem here?” Mr Quilty asked the audience. “It’s enormous.”

- Worth noting, the AusVetPlan is currently undergoing a review, but until that is completed, these are the circumstances that would apply.

Monday: Why Australia’s domestic consumer market would be critical for softening the blow, in the event of an FMD outbreak.

HAVE YOUR SAY