AFRICAN Swine Fever outbreaks have been confirmed in East Timor by the OIE, the World Organisation for Animal Health.

The report last Friday identified 100 outbreaks with 405 deaths reported in the East Timor municipalities of Baucau and Liquica. The first outbreak occurred on September 9th and as stated since then a total of 100 outbreaks have occurred.

It should be noted that East Timor has a small pig population of close to 400,000 head.

The concern for Australia is the closeness of East Timor to Australia – the distance from the two East Timor municipalities and Darwin is only 650 km.

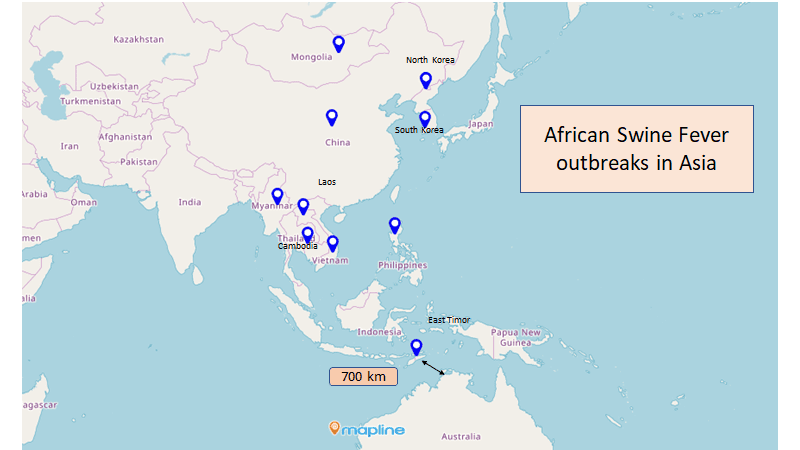

East Timor is the tenth nation in Asia to now have the disease. The other nations include; China, Vietnam, Laos, Maynmar, North Korea, South Korea, Mongolia, Philippines, Cambodia and now East Timor – with a combined total of 522 million pigs from an estimated global population of 770 million pigs (source: Statista).

As stated in my previous paper the recent accelerated rate of contamination in China could see an estimated 70% of all pigs gone by the end of 2019 – if using the same percentage of infection across all of Asia over a similar 16 month period this would equate to 365 million head or 48% of global pigs would be gone by mid next year.

| Country | 2017/18 baseline population estimate | Date disease announced |

| China | 441 | August, 2018 |

| Mongolia | 0.05 | January, 2019 |

| Vietnam | 27 | February, 2019 |

| North Korea | 3 | April, 2019 |

| Cambodia | 2 | April,2019 |

| Laos | 4 | June, 2019 |

| Myanmar | 18 | August, 2019 |

| Philippines | 12.5 | September, 2019 |

| South Korea | 11 | September, 2019 |

| East Timor | 0.4 | September, 2019 |

| Total | 522 million |

The closest two countries to East Timor with African swine fever are 1500 km to the Philippines and 2000 km to Vietnam and brings the disease within an uncomfortable close proximity of 650 km to Australia.

The cause of contamination is still unknown but if other infected countries are a guide, then humans are the likely cause of migration via either contaminated food products or potentially exported contaminated feed (though yet to be proven) or simply present on clothing and shoes and carried into East Timor from an infected country.

On Friday the Timor-Leste Council of Ministers issued a press release stating:

“The Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries in office, Fidelis Leite Magalhães, made a presentation to the Council of Ministers on the disease that has caused the deaths of hundreds of pigs in the country. Samples were taken from these animals and sent for laboratory analysis in Australia confirming that these animals suffer from African swine fever. This disease is highly contagious among animals, not producing effects on humans and has affected several Asian countries. The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, in collaboration with the Government of Australia, has taken all necessary measures to limit the effects of this outbreak, for which there is still no remedy, cure or vaccine.'”

Comment: The closeness of African Swine Fever to Australia is very concerning and with the small size of the East Timorese pig herd it is hoped that preventative measures can be put in place in a timely manner.

In 2015, a joint Australian Department of Agriculture and Water Resources conducted animal health surveys with East Timor Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries – in addition, Australia provided a wide range of biosecurity training in exotic diseases to East Timorese animal health staff. Joint biosecurity public awareness activities were held in East Timor villages and East Timorese biosecurity workers were trained in understanding risk factors for exotic diseases such as African Swine Fever, surveillance and appropriate animal health management practices to manage outbreaks.

This ongoing close working relationship between Australia and East Timor on prevention of exotic diseases hopefully will prove to be critical in keeping African swine fever at bay and from entering Australia.

Australia’s Emergency Animal Disease Bulletin No. 120

Australia’s Agricultural Department issued this bulletin on September 14th, 2018 – one month after the first outbreak in China – it reads as follows:

Keeping Australia ASF free

Australia maintains an ASF-free status and greatly reduces the risk of incursion through the enforcement of strict biosecurity policies. Australia’s focus is on ensuring that the level of risk in products that arrive at its borders are already managed to levels that are acceptable. Stringent, scientifically informed import regulations exist for pork and pork products.

In addition, swill feeding is illegal under legislation in Australia. At the federal level, the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources applies rigorous inspection protocols at Australia’s national borders, and conducts off-shore disease surveillance and risk mitigation activities in Australia’s close neighbours, including Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea.

The risk of introduction

Illegal importation of ASFV-infected pig products or genetic material remains the most likely source for entry of ASF into Australia. Although swill feeding is prohibited, unlawful or inadvertent feeding of imported infected products to domestic or feral pigs presents the greatest risk, and is believed to be the cause of the first ASF outbreak outside of Africa. Contaminated products may arrive from endemic countries via commercial aircrafts or ships, the international postal service, or waste from fishing vessels. Provided Australia’s modern intensive piggeries continue to practice a high level of biosecurity, the most likely sites of entry for ASF would be smaller commercial or backyard establishments, or scavenging feral pigs.

Comment: It should be noted that back in 2015 Australia commenced a research project with East Timor Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries on focusing on smallholder pig health and production systems in eastern Indonesia and East Timor which included a focus on the control of classical swine fever. Classical swine fever is different to African swine fever in that there is a vaccine for classical swine fever but there is none for African swine fever – nonetheless this background in other related diseases will hopefully prove to be invaluable when trying to control this disease in East Timor.

Australian Agricultural Minister calls for an ASF round table discussion (recap)

The following are a recap of the notes I published in my last report which I believe have as much relevance today given this news of how close African Swine Fever is to Australia.

On September 6th, I attended a meeting at Parliament House in Canberra that brought together key meat industry stakeholders and government agencies that oversee bio-security in Australia to discuss steps required to prevent ASF from entering Australia. I participated on a panel to give a global ASF outlook from a commercial trade view point.

Some of the key messages of the day were as follows:

- Several state government veterinary agencies feel under resourced and have raised the need for better funding of their agencies to ensure adequate disease risk management procedures are in place.

- There was general consensus that the work done in preventing ASF and any contingency planning should apply across all diseases including foot and mouth disease.

- It became apparent that the co-ordination of state and federal agencies and industry with regards to future preventing and/or controlling diseases is a complex task that cannot happen overnight but will require long term planning with defined structures and roles that will ensure effective responses to any potential outbreaks.

- Australian airports remain potentially the most likely form of entry of diseases and therefore where resources such as detector dogs are most required – the number of dogs performing this role was quoted as being 80 in 2012 to now 36 in 2019. It was outlined that even though numbers of dogs are less today than seven years ago, the multiple roles these dogs perform at both sea ports, postal centers and airports means that these are better utilised today than ever before and that this number of dogs is adequate for the various roles they play.

- Each year Australia receives approximately 20 million travelers through our international airports. The Department screens about 6.3 million travelers per year of which 4% are deemed to carry actionable high risk bio-security material or 250,000 people. This volume of high risk passengers is stretching to the limit our custom and bio-security officials across all Australian airports.

- The shortage of pork in China was highlighted due to the large hog inventory losses in China and the important role that Australian imported beef and sheepmeat are playing to help fill this void. It was requested that the Minister continue to push the China counterparts on having more meat works in Australia China approved, a larger number of approved chilled beef plants and the need to have the discretionary safeguard removed so as to avoid on going triggering and higher tariffs.

- Last but not least, I was impressed to see Minister McKenzie stay for the entire day and be fully engaged in all aspects of the discussion – it showed to me a real genuine concern for the threat of ASF to Australia.

Australia’s pork industry compared to other countries is relatively small with approximately 4.85 million pigs produced a year yielding close to 360,000 tonnes of pig meat a year – of this close to 8 percent is exported with Singapore being our largest market.

Each year Australian’s consumes approximately 24.2 kg of pork per person and it is the impact on Australia’s pork domestic market that is what is so important in terms the threat of ASF and the need to protect this market.

Comment: The need for more funding at both a state and federal level was a clear message on the day of this round table discussion – chief veterinary officers both federally and state all spoke of the stretched resources and the concern each had for there ability to manage an outbreak of African swine fever.

The other key message was the need to put in place well defined structures and roles of state and federal agencies and how to best work with the private sector to ensure a well co-ordinated response to African swine fever. Now that the disease is on Australia’s door step most present at the meeting would agree there is an increased urgency to have this disease prevention planning framework finalised.

Feral pigs in Australia

It has been estimated that 24 million feral pigs live in Australia and pose a major threat as a potential carrier of African Swine Fever should it ever enter Australia.

In Europe feral pigs (wild boars) are the main vectors that spread African Swine Fever and recent research in Australia on our own feral pig population by University of New England has shown that when monitoring 120 feral pigs using satellite collars discovered that feral pigs do not travel far food and water and highlight these animals are creatures of habit – critical information is finding a means to control them. In addition, the research revealed a disturbing number of pigs infected with serious diseases such as leptospirosis (25% of pigs tested) and brucellosis (4 to 5% of pigs tested).

The Australian domestic pork industry has been estimated to be worth $50 billion and must be protected.

How do Europe and Asia’s African Swine Fever outbreaks differ?

There is an important difference between the spread of African swine fever in Europe compared to Asia and it is best reflected in the rate of spreading of the disease.

In Europe the main vector that has spread African swine fever are wild boars (feral pigs) and was first detected in Portugal in 1957 and spread through most of Western Europe over the following 30 years. In Eastern Europe the virus was first detected Georgia in 2007 and eventually reached Poland in 2014 where it has remained in the wild boar population ever since – today 14 countries in Europe have the disease which includes Russia, Poland, Belraus, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldava and Serbia.

The European Food Safety Authority has identified that movement of infected animals (Boars and/or domestic pigs), contaminated pork products and the illegal disposal of carcasses are the most significant means of spreading the disease.

Denmark back in March this year announced it would build a 70 km pig-proof fence between Germany and itself to prevent the risk of wild boar from entering even though Germany has not got the disease itself but the fear is that with surrounding countries such as Belgium, the Czech Republic and Poland with disease many believe it is just a matter of time before it crosses the border.

In Germany over 800,000 wild boars were shot in the 2017/18 year as a means of prevention – France has also been culling wild boars. This focus is based on strong evidence that once the disease is well established in the wild boar population it is almost impossible to remove as has been the case in the Baltic States of eastern Europe and Russia.

As a result the spread of African swine fever in Europe has been at a much slower pace than in Asia as the controlling of wild boars and an incraese in biosecurity systems has kept the disease in certain regions at bay.

In contrast, Asia’s spread of the disease has been much more significant due to cultural practices and the high density of pigs throughout most of Asia and in particular China. In just over 12 months we have seen the disease spread to every province in China and nine other Asian countries at a breathtaking rate that has exceeded any rate of spread in Europe.

The prevalence of backyard pigs in high proportion, the unregulated use of swill to feed pigs both at home and in commercial operations, low levels of biosecurity and the presence of African sine fever in the food chain have all contributed to the rapid spread through Asia.

One of the most concerning periods of spreading the disease in Asia is during holiday periods when people movement increases dramatically – during celebrations infected food unknowingly is often brought as gifts or the disease is present on the clothes, shoes or vehicles of workers. To restrict people movement is almost impossible.

Comment: So the disease spread in Europe is mainly due to wild boars as the main vector which has seen the disease in certain areas been kept at bay but in Asia the spread of disease is via humans and the cultural practices of feeding swill to backyard pigs, travel and contaminated food products all of which are much more difficult to control.

There are lessons learnt from both Asia and Europe on the spread of African swine fever with I believe elements of both regions that need to be noted. The similarity with Asia, like all countries, is the human factor whereby the disease is unknowingly brought in from infected countries either via the footwear and clothes the traveler wears or via contaminated food products they bring in. But once in Australia I believe the real threat is from our feral pig population and like Europe the degree of the spread and where it occurs will depend on our ability to manage these feral pigs.

The cultural issues of Asia that have led to the rapid spread of the disease such as contaminated feed swill, a high prevalence of backyard pigs, a contaminated food supply system and low biosecurity do not exist in Australia. Given the high biosecurity systems that exist today in Australia and the likely elevated systems that would be put in place – the Asia like rate of spreading in our domestic pig population is I believe highly unlikely.

Conclusion

The presence of African Swine Fever in East Timor is alarming to say the least, having jumped 1500-2000 km and puts the disease on Australia’s door step.

The main cause of distribution continues to be humans and there is now a genuine need to heighten security and increase resources in Australia’s bio-security prevention procedures to ensure the disease does not enter Australia or if it does it is well managed – all state and federal chief veterinarians voiced there same concerns on the need for more resources in Canberra four weeks ago.

The round table discussion that Agriculture Minister McKenzie organised on September 6th, has proven to be valuable in identifying priorities and the needs of both government agencies and the private sector – to me it is critical to build on this meeting.

The lessons learnt from both Asia and Europe is that Asia is the most likely source of where the disease may enter from but this is likely to be more due to the movement of people than somehow coming across the water from East Timor. The high traffic of Asian visitors and the potential contamination of food, clothes or shoes are the most likely sources of the disease.

If the disease should ever enter Australia it is the lessons from Europe that may have the most relevance – understanding how they manage there wild boar populations that could prove to be invaluable and what has been done to improve the biosecurity systems within each European country to contain the virus.

The erratic movement of African Swine Fever reinforces not only Australia’s vulnerability but also many other countries such as North America – the issues that I have raised in this paper to me are just as relevant to North America as they are to Australia, only multiply the impact by many many times.

HAVE YOUR SAY