QDAF principal research scientist beef extension Joe Rolfe, left, with Mike Pratt of Waroona Pastoral Company, QDAF principal research scientist beef Dr Maree Bowen and Colin Burnett from Lara Downs Station.

QUEENSLAND graziers who can alter their beef cattle operations to cope with challenging seasons – even by adding sheep and goats – are more likely to maintain profitability and survive drought.

Visitors to Beef 2021 heard about some ways to achieve both goals in Monday’s Improving profitability and resilience of grazing businesses session.

Leading the presentation was Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (QDAF) principal research scientist beef Dr Maree Bowen, who said knowing when and how to destock and restock were among the major challenges.

With input on strategies and experiences from graziers Colin Burnett of Lara Downs Station at Julia Creek, and Mike Pratt of Waroona Pastoral Company at Longreach, the crowd got some pointers derived from long-term QDAF economic analysis.

Heading the list of successful strategies was changing the turn-off weights of cattle, and adjusting the ratio of breeders and trade cattle.

Across northern Australia, addressing phosphorous deficiencies in cattle, and introducing perennial legumes like leucaena and stylo were alos found to be consistently profitable strategies to counter the impact of adverse seasons.

Research looked at north and western Queensland, or 60 per cent of the state, with hubs at Charleville; Georgetown; Longreach, and Richmond.

“We could identify strategies in each region that could improve our situation.”

Dr Bowen said whole-farm economic modelling was done on representative properties chosen by QDAF and the Northern Territory Department of Primary Industries to examine a range of alternative management strategies over a 30-year time period.

It included one example property at Julia Creek on the Northern Downs which changed from selling steers as weaners to growing them out to 31 months, and returned a $70,000 per annum benefit.

Also on the Northern Downs, changing from a breeding operation to a steer-growing one has delivered a $62,500/annum benefit.

Sheep and goats can improve profitability

Dr Bowen said targeting a breeder body condition of equal to or greater than three when going into drought was important to identify those breeders that should be retained during destocking.

She said determining the optimum cull age for females was also important, and could be assessed with the help of free-to-use Breedcow and Dynamo software.

“In the response to drought and disaster, it’s really important to assess all classes and livestock of livestock for sale.

“That’s because you can get really surprising results.”

Some strategies had a negligible effect and added roughly $5000 per annum to herd profit, and Dr Bowen said others had “quite a large negative effect on profit”.

Poor performers included feeding and sometimes growing inputs including molasses, silage, grain, forage sorghum or forage oats failed.

The experience of Mr Pratt bore out the modelling result which said small ruminants can significantly improve profitability.

Dr Bowen said the introducing of meat sheep, meat goats or a self-replacing merino wool flock could all improve average profitability by smoothing income over time.

“Wool and met sheep prices may not move in parallel”.

Waroona Pastoral Company principal Mike Pratt presents at Beef 201

Adding sheep and goats to the mix has also proved highly successful for some, including Mr Pratt. He is a member of the Agforce Sheep and Wool Board and has had broad experience with running grazing enterprises across Queensland and using agistment.

The Pratts have had a self-replacing Merino flock since 1990 and for 20 years ran Brahman breeders terminally crossed to Angus bulls.

He said “the penny dropped” that small ruminants could be more profitable, and were compatible with the local climate.

“It has forgotten to rain far too often.”

In 2016, the Pratts got out of breeding cattle and into goats, and now opportunity background cattle, and run commercial goats and Merinos.

“Two eight-year droughts in 20 years would normally sink most businesses.”

The Pratts are still operating successfully, and say agistment is part of their management plan up to 60pc of the time.

“We were able to find good agistment for our sheep or cattle.”

“You can run a profitable cattle-breeding enterprise, but you need to agist.”

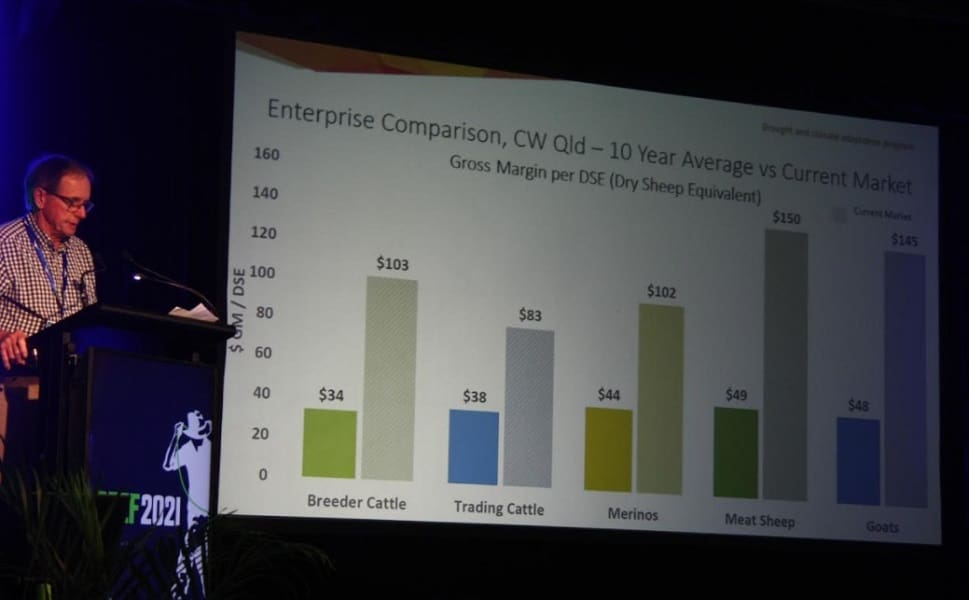

The Pratts’ experience has been borne out by QDAF enterprise comparison figures, which put the gross margin per dry sheep equivalent on a 10-year average at $49 for meat sheep and $48 for goats, with breeding cattle at $34.

Exclusion fencing is crucial

Mr Pratt said the wool downturn of the early 1990s forced many producers into cattle because sheep were “worth nothing”, and small ruminants were now worth revisiting.

However, exclusion fencing to protect from wild dogs was a must in south-west Queensland particularly.

The Pratts’ stand-out capital item is exclusion fencing, and they have spent $540,000, or $5600 per kilometre over 96km, which equates to $21/ha, on the improvement. He said it kept small stock safe, and kangaroos out, with 10 of them being equivalent to seven sheep or one steer.

“We get a 100pc return on investment in a 12-month period on goats and meat sheep.”

“If you want to diversity, you can run meet sheep or goat pretty much anywhere you can run cattle.”

Location has a bearing on resilience

QDAF modelling said production systems that were less flexible were also found to attract greater risk and be less resilient. This included Wagyu production and organic beef.

Mr Burnett said his family’s property on the Northern Downs dealt with a 46pc deviation from mean on average annual rainfall.

“We’re up and down a lot.”

Colin Burnett of Lara Downs Station presents at Beef 2021

In the 2019 floods, Lara Downs lost some of its cattle and 45km of fence when it had 968mm of rain in 12 days.

“We didn’t really have any paddock we could use for a couple of months.”

The Burnett family moved north from Belyando in central Queensland in 2000, and changed from a fattening-only enterprise.

“Dad was a bullock man, and we kept every steer through to about three years old.”

These days, the family aims to turn off a percentage of bullocks, and shies away from agistment.

They run 9000 head of Brahman-cross cattle, and supply the live and slaughter markets.

“One hour north of Julia Creek…is suited to that one quarter of breeders and no more.”

Mr Burnett said running more breeders to occupy up to one third of the property came at a cost in terms of poorer calving and stock condition if the season cut out.

“We don’t want to get caught selling light breeders on the cheap.”

They grow steers out to around 30 months to ideally dress out at around 320 kilograms, and grow heifers out also.

“We’ve always got some slaughter in the years where younger cattle aren’t worth a lot.

Both Dr Bowen and Mr Burnett spoke about the “weaner trap”, when cashflow can become dependent on selling cattle at a younger age.

“It can be difficult to get back to older ages,” Dr Bowen said.

However, selling of weaners should not be ruled out on principal.

“We’ve definitely sold some weaners but we haven’t gotten out of older cattle,” Mr Burnett said.

On Lara Downs, heavier Brahman cattle get two HGP injections.

“That’s the holy grail, average four teeth dressing 320kg, and meeting meatworks specifications.

“We’ve been able to do that through the wet and the dry.”

As the QDAF modelling suggests, organic production does not suit every enterprise, and being in a tick area has dissuaded the Burnett family from going down that path.

“We’re in ticky country; there’s a few things stop us going organic.”

Prickly acacia is another issue.

“There’s infestation across 20pc of Lara.

“We spent $10,000 a year and had to expand it to $20,000 a year.”

The shade prickly acacia creates severely reduces the amount of groundcover which will grow in paddocks.

“It’s a big bugbear of mine.

“As Maree’s work has shown, any money you spend on acacia has a return.

“From Hughenden to Cloncurry, it’s obviously a massive problem.”

Lara Downs was in drought last year, and Mr Burnett said all its sale cattle had been offloaded by August 2020 and the property became “basically dormant”.

In the low-interest environment and after the 2019 flood, Mr Burnett diversified into earthmoving and real estate to make the most of opportunities off the farm.

“When there’s no money in beef, we think there’s no money in the region.”

“Management obviously has to be flexible.

“That’s something I wasn’t that good at.”

As a Nuffield Scholar, and now an Advancing Beef Leader, Mr Burnett said networking and personal development were important.

HAVE YOUR SAY