IN 2014, the sheep industry in western Queensland was at a crisis point, with wild dogs decimating flocks and causing generational wool growers to exit the industry and run cattle.

Trapping, shooting and baiting with 1080 were not making a difference and it was decided predator fencing was the only way the industry could continue.

Two models of fencing were identified as the best options to keep wild dogs and feral pigs out: a large-scale regional fence that enclosed multiple local council shire areas or cluster fencing that enclosed more than two properties.

After much debate it was decided the cluster fencing model would be the most effective at reducing wild dog and feral pig numbers.

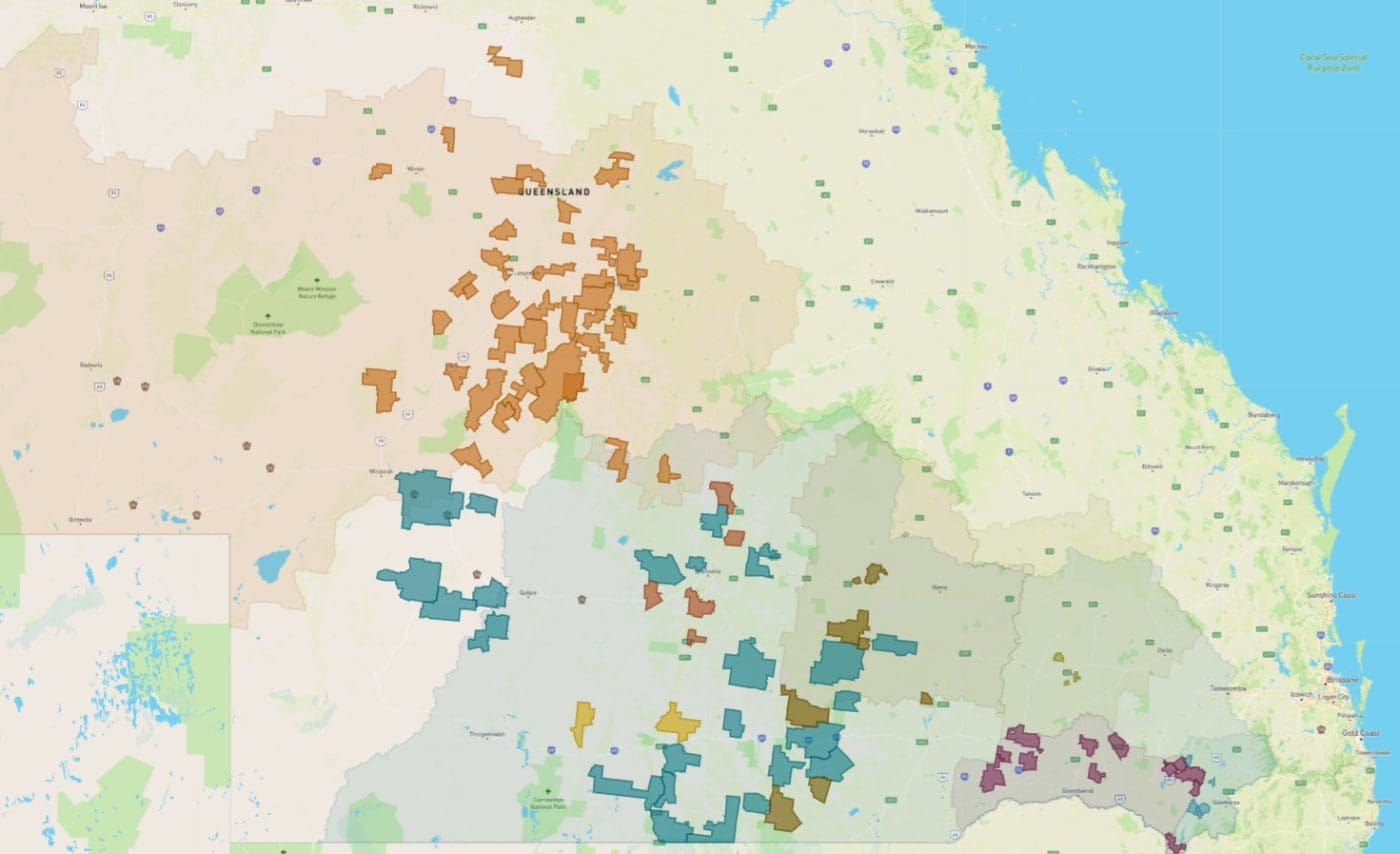

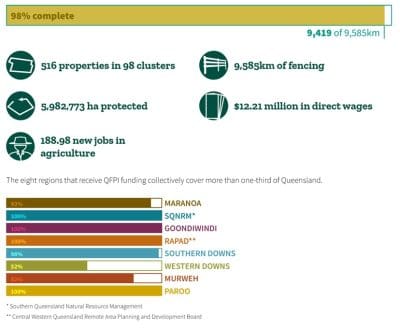

Since then, the Queensland’s Government’s Feral Pest Initiative Cluster Fencing program has helped build more than 9400km of predator fencing across the state, with funding for another 100km still available in some council areas.

*There was also funding from the Federal Government and landholders who funded their own fence, so these figures are not inclusive of those fences.

Morgan Gronold, Acting CEO of the Remote Area Planning and Development Board oversaw the program delivery for several councils in Central Western Queensland.

“The key components to the success of the initiative were firstly it had to be voluntary, landholders had to partner with their neighbours and put a proposal together, which included a partnership agreement for maintenance, to secure funding,” he said.

“If it was a mandatory or regulated initiative, I don’t believe it would have been as successful.

“The other factor was the fencing specifications were very clear; there was a minimum height and netting requirement which has meant there is consistency across the region in the fences.

“Thirdly, landowners had to have skin in the game and contribute the difference after the government subsidy.”

Sheep numbers have increased from fencing

The Queensland Government has a website, ‘Not Just A Fence’ which details where the fences have been built, how many stock numbers have changed, how many jobs the fences have created and more.

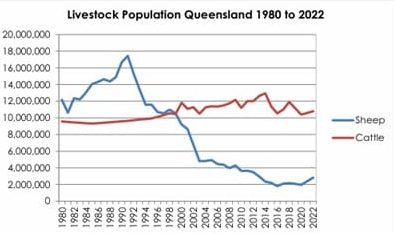

“Sheep numbers in Queensland declined from 8.5 million in 2001, to a low of 1.8 million in 2016 and have since recovered to 2.8 million in 2021.

“Over the period 2001 to 2016 lambing rates in QFPI regions had declined by around 33 percent.

“The majority of sheep producers who now have exclusion fences have seen their lambing rates return to levels experienced prior to 2001.”

The website states the total investment has been over $91 million, $28 million from the state government and over $63 million from landholders.

Andrew Martin is a wool grower near Tambo and was one of the first to build a cluster fence.

He partnered with more than 20 neighbours to enclose one million acres.

“We bought Macfarlane in 2012 and in that first 12 months we caught 137 dogs, that’s just what we caught. And neighbours were getting similar numbers,” said Mr Martin.

“After the initial cluster was built, we partnered with four neighbours to further fence ourselves into a smaller cluster.

“The year before we fenced, we got a seven percent lambing. The year after our fence was built, we got close to 80pc of lambs and caught four dogs and had no pigs.

“It was immediately worth it. We had a 108pc lambing, 100pc lambing and a 98pc lambing in a row.

“My family has been doing merinos around Tambo fo140 years and to my knowledge if that is not the first time, it is one of very few occurrences to have those lambings back to back.”

Mr Martin said the fence has also helped native animals.

“Ever since the fence was built the brolgas are having two chicks, the swans are having three or four cygnets, I have never seen so many goannas,” he said.

“I call them inclusion fences because they include good economic outcomes with good environmental outcomes.”

Cost of fencing

When the Queensland Government model of cluster fencing first started in 2015, the state would contribute one-third of the cost which was worked out to be $2700 per kilometre while the landowner had to fund the remaining two-thirds, (a total cost of over $8000 per km).

Given the increases in labour and materials Beef Central has been told the cost for a predator proof fence is now $15,000 to $20,000 per km.

On top of the increase in cost is the waiting times for a fencing contractor, with one telling Beef Central the earliest they can book work is mid-2026.

Off the back of the success of the QFPI cluster fencing program, the Longreach Regional Council launched its own initiative where landholders can borrow the money to fence their individual properties off the council and pay it back through their rates.

“The scheme operates on a similar model to the rural electrification scheme in the 1950’s,” said Tony Rayner, Mayor of Longreach Regional Council.

“Council secured a loan from the Queensland Treasury Corporation to fund the scheme, and the costs of the scheme are paid by participating landholders through a special rate levied over a 22-year period, making the scheme financially sustainable and equitable.”

There are 60 properties currently participating in the scheme.

These are the long-term benefits of exclusion fencing according to RAPAD:

- Control, confidence and investment – landholders felt they regained control of their properties and livestock which boosted confidence to invest not only in sheep but also other parts of their business.

- Increases in production.

- Better able to manage pasture.

- More native wildlife – goannas, brolgas, emus.

- High agistment rates for country behind a predator proof fence.

- Improved mental health.

- More time – all of the time that was spent chasing dogs can now be put towards other more positive parts of the business.

Has fencing ever taken off in other states?

Fencing is not a new concept for protecting livestock from predators, the Dingo Fence was erected during the 1880’s to protect sheep from wild dogs and it still exists today stretching across 5,614km in Qld, NSW and SA.

But fencing has evolved in each state with some moving towards the cluster models, while other states have extended existing linear fences.

New South Wales

The NSW Government was contacted to see if cluster fencing had been adopted, but did not respond.

There is however a 600km dog-proof border fence along the NSW, Qld and SA borders.

The fence is crucial in keeping dingoes and wild dogs out of sheep, goat, and cattle grazing areas in western NSW according to the NSW Government website.

In 2023 a 32km extension to the NSW Border Wild Dog Fence closed the existing gap with the SA dog fence.

Victoria

The Victorian Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action said it works closely with local communities to appropriately balance dingo conservation and the protection of livestock.

“The Victorian Government has invested over $2.5 million in a support package, including funding trials and research on non-lethal dingo management strategies (including exclusion fencing and guardian animals) aimed at developing practices to protect livestock while safeguarding the vulnerable dingo population from extinction in the northwest of Victoria,” a department spokesperson said.

“The use of fencing continues to be encouraged as part of Victoria’s Vertebrate Species Management Program.”

South Australia

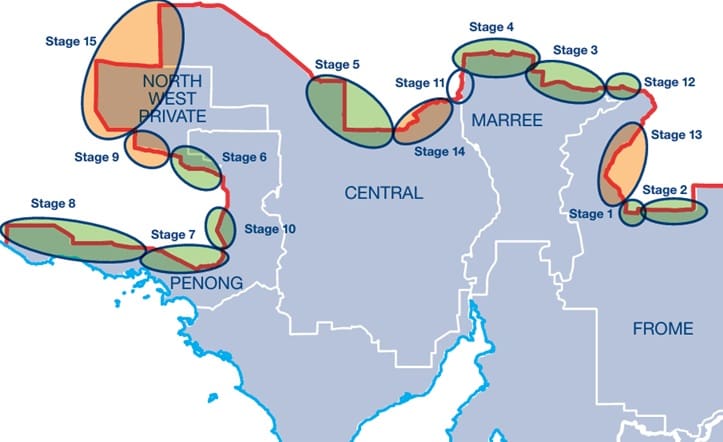

South Australia has a Dog Fence which stretches across 2150km from the Great Australian Bight near Fowlers Bay to the New South Wales border.

The Dog Fence protects South Australia’s $4.3 billion livestock industry by stopping wild dogs from migrating into land used for sheep production. This area is known as the sheep zone.

More than two-thirds of the Dog Fence is being rebuilt, as 1600km was more than 100 years old.

The rebuilt fence stands approximately 160cm high and has a 40cm apron. Electric fencing has been applied where additional deterrence is required.

Of the rebuilt fence, about 32km is fully electrified to deter wild dogs, approximately 300km (both sides, 600km in total) to deter wombats, and 520km of elevated or offset electrified fencing to deter camels.

The rebuild is funded by $10 million from the Federal Government, $13 million from the SA Government and $6 million from the livestock industry.

It is expected to be complete by June 2026.

Western Australia

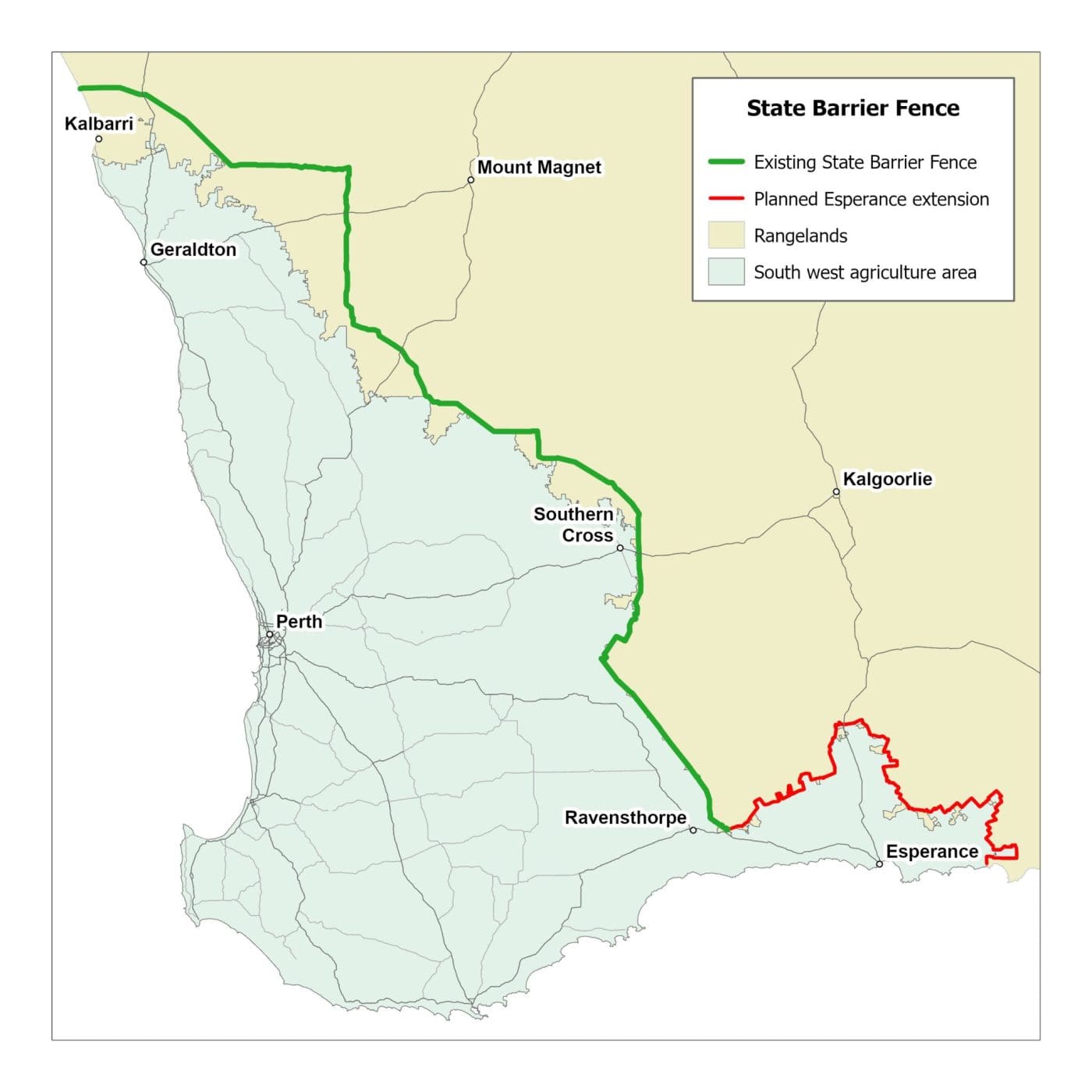

Western Australia has a 1200km State Barrier Fence that plays an important role in preventing animal pests, such as wild dogs and emus, from impacting the state’s agricultural sector, according to the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

The fence is currently being extended by 660km to help protect livestock businesses in WA’s south-east.

The State Barrier Fence is a key component of the WA Wild Dog Action Plan.

In addition to the fence, two Vermin Proof Cells have been constructed by community groups, with WA Government support, in the Murchison region of the State’s southern rangelands.

The National Wild Dog Action Plan website stated the Murchison Regional Vermin Cell saw 55 pastoral leases and 6.5 million hectares enclosed with 1400km of wild dog proof vermin fence that over time will enable a return to small stock production.

Exclusion fencing is not considered to be required in Tasmania due to the limited nature of the problem.

HAVE YOUR SAY