Seasonal flooding at Tanbar Station near Windorah in Queensland. Photo: File

THE State of the Climate Report 2022 has found changes to weather and climate extremes are happening at an increased pace across Australia.

Released this week by CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology, the biennial report shows an increase in extreme heat events, intense heavy rainfall, longer fire seasons and sea level rise.

The report draws on the latest climate monitoring, science and projection information to detail Australia’s changing climate now and into the future.

The report shows heavy rainfall events are becoming more intense and the number of short-duration heavy rainfall events is expected to increase in the future.

This has been evidenced during La Niña events in 2021-22, when eastern Australia experienced one of its most significant flood periods ever observed.

The Bureau of Meteorology’s manager of climate environmental prediction services, Karl Braganza, said the report projected increases in air temperatures, more heat extremes and fewer cold extremes in coming decades.

“Australia’s climate has warmed on average by 1.47 degrees since 1910,” Dr Braganza said, adding that contrasting rainfall trends across the north and the south of the country.

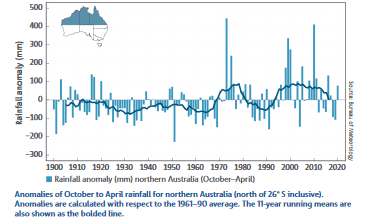

“There’s been an overall decline in rainfall between April and October across southern Australia in recent decades, but in northern Australia, rainfall has increased across the region since the 1970s.”

“There’s been an overall decline in rainfall between April and October across southern Australia in recent decades, but in northern Australia, rainfall has increased across the region since the 1970s.”

Dr Braganza said the length of fire seasons has increased across the country in recent decades.

“We’re expecting to see longer fire seasons in the future for the south and east, and an increase in the number of dangerous fire weather days,” he said.

Wetter wet season

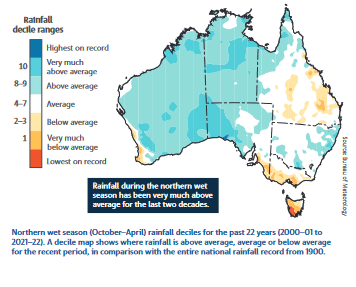

The report says northern Australia has been wetter in the 21st century than in the 20th century, across all seasons, especially in the north-west during the north’s wet season spanning October-April.

However, rainfall variability remains high, with the 2010s being not as far above average as the 2000s.

However, rainfall variability remains high, with the 2010s being not as far above average as the 2000s.

In southern Queensland, there has been a trend towards lower rainfall throughout the year, particularly during the past decade.

Warm-season rainfall has also been below average in parts of Tasmania and the south-east and south-west coasts of mainland Australia in recent decades.

Drier in south-east

The report said there has been a decline of around 15 per cent in April-October rainfall in the south-west of Australia since 1970.

Across the same region, May-July rainfall has seen the largest decrease, of around 19pc since 1970.

South-eastern Australia has seen a drop of around 10pc in April-October rainfall since the late 1990s.

In 19 of the 22 years from 2000 to 2021, April-October rainfall in southern Australia has been below the 1961-90 average, which the report says is due to a combination of natural variability on decadal timescales and changes in large-scale circulation caused by an increase in greenhouse gas emissions.

The drying trend in southern Australia is most evident in the south-west and south-east of the country, and the recent drying across these regions is the most sustained large-scale change in observed rainfall since widespread observations became available in the late 1880s.

The trend is particularly strong for May-July over south-west Western Australia, with rainfall since 1970 around 19pc less than the average from 1900-69; over the full April-October season, the decline over the same period is around 15pc.

Since 2000, this decline has increased to around 27pc, despite relatively high cool-season rainfall during 2021.

For the south-east of the continent, average April-October rainfall for 2000-21 was around 10pc lower than the 1900-99 period.

The Millennium Drought was a major influence on this, affecting rainfall totals across the region from 1997-2009.

However, cool-season rainfall totals are still 7pc below the 1900-99 average in the years since 2010.

The only years with above-average cool season rainfall in south-east Australia in the past two decades were 2010, 2016 and 2020; these occurred during the La Niña events of 2010-12 and 2020-22, and the strong negative Indian Ocean Dipole event of 2016.

April-October rain falls in the growing season for winter crops, and it is also when peak streamflow occurs in most catchments in south-eastern Australia, as cool-season rainfall is generally more effective than warm-season rainfall in generating runoff.

The declining trend in rainfall during this period is associated with a trend towards higher surface atmospheric pressure in the region and a shift in large-scale weather patterns to more highs, fewer lows, and a reduction in the number of cold fronts that produce rainfall.

Warming temperatures

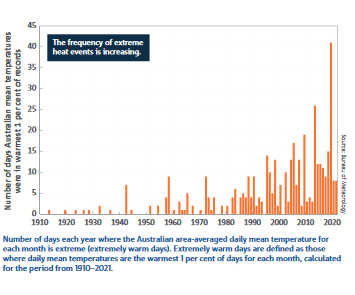

The report shows every decade since 1950 has been warmer than preceding decades, and says warming in Australia is consistent with global trends, with the degree of warming similar to the overall average across the world’s land areas.

Australia’s warmest year on record was 2019, with the eight years from 2013 to 2020 all rank among the 10 warmest years on record.

The long-term warming trend means that most years are now warmer than almost any observed during the 20th century.

The long-term warming trend means that most years are now warmer than almost any observed during the 20th century.

Warming has been observed across Australia in all months, with both day and night-time temperatures increasing.

This shift is accompanied by an increased number of extreme nationally averaged daily heat events across all months, including a greater frequency of very hot days in summer.

For example, 2019 experienced 41 extremely warm days, about triple the highest number in any year prior to 2000.

Also in 2019, there were 33 days when the national daily average maximum temperatures exceeded 39 degrees Celsius, a larger number than seen in the 59 years from 1960 to 2018 combined.

Increasing trends in extreme heat are observed at locations across all of Australia.

Extreme heat has caused more deaths in Australia than any other natural hazard and has major impacts on ecosystems and infrastructure.

There has also been an increase in the frequency of months that are much warmer than usual. Very high monthly maximum temperatures that occurred nearly 2pc of the time in 1960-89 occurred more than 11pc of the time from 2007-21.

Very high monthly night-time temperatures are a major contributor to heat stress, and occurred nearly 2pc of the time in 1960-89 but now occur around 10pc of the time.

The frequencies of extremely cold days and nights have declined across Australia.

An exception is for extremely cold nights in parts of south-east and south-west Australia, which have seen significant cool-season drying, and hence more clear winter nights, which cause colder nights due to increased heat loss from the ground

The frequency of frost in these parts has been relatively unchanged since the 1980s.

Impact on agriculture

CSIRO agriculture and food director Michael Robertson said threats caused by climate change, including extreme rainfall, droughts, heatwaves and bushfires, are already impacting Australia’s agricultural industry, affecting food production and supply chains.

“Historically the sector has shown its ability to adapt to changes in climate, but we have an important role to play at CSIRO to help our farmers to build on that, navigating the growing climate risks to ensure long-term viability of rural enterprises and communities,” Dr Robertson said.

The organisation is already seeking to do this through initiatives such as Climate Services for Agriculture, which provides historical weather and climate projections on a 5km grid to allow farmers to see how climate is changing in ways relevant to what they produce.

New high for greenhouse gas

CSIRO’s Climate Science Centre director Jaci Brown said concentrations of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, are at the highest levels seen on Earth in at least two million years.

“The concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are continuing to rise, and this is causing Australia’s climate to warm,” Dr Brown said.

Dr Brown said the report documents the continuing acidification of the oceans around Australia, which have also warmed by more than one degree since 1900.

“The warming of our oceans is contributing to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves, and this trend is expected to continue into the future,” Dr Brown said.

“We’re seeing mass coral bleaching events more often, and this year, for the first time, we’ve seen a mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef during a La Niña year.”

“The rate of sea level rise varies around Australia’s coastlines, but the north and south-east have experienced the most significant increases.”

State of the Climate 2022 is the seventh report in the series.

Source: CSIRO

HAVE YOUR SAY