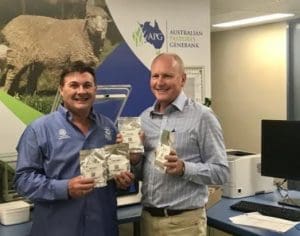

Australian Pastures Genebank curator, Steve Hughes, with Australian chief plant protection officer, Dr Kim Ritman.

AUSTRALIAN agricultural seeds are destined for a Norwegian ‘doomsday’ vault as part of a global effort to preserve and protect vital stocks of plant material.

Australia is about to send a consignment of crop and pasture seeds for storage in the so-called ‘doomsday’ vault at Svalbard in Norway.

Two pallets containing 9000 crop seed accessions from the Australian Grains Genebank at Horsham, Victoria, and 25,000 pasture seed accessions from the Australian Pastures Genebank in Adelaide, South Australia, will be flown to Norway next month for deposit in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

The Svalbard vault, which is built 120 metres into the side of a mountain above the Arctic Circle and currently contains 890,000 samples, is a natural freezer designed to preserve the world’s collection of seeds and protect them from global catastrophe.

Australian chief plant protection officer, Dr Kim Ritman, said the consignment was not the full collection from both genebanks, but it added to 10,000 accessions that were taken over in 2014 as part of Australia’s first deposit into the vault.

Protection for Australian pasture and grain history

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault holds the world’s seed collection deep inside a mountain in Norway.

Dr Ritman said the transfer of seeds from Australia’s seed vaults to Norway would provide additional protection to a number of significant seed varieties that represented Australia’s pasture and grain crop history.

“The Australian Pastures Genebank in South Australia and the Australian Grains Genebank in Victoria play critical roles in underpinning agricultural productivity growth through genetic improvement and protecting our seeds for future generations,” Dr Ritman said.

“While Australian collections feature a variety of unique and valuable seed stocks, the vault in Norway acts as a back-up to ensure future generations enjoy the best possible chance of overcoming the potential for natural or man-made disasters that may arise through challenges like climate change, population growth and even war.

“While more than 1700 genebanks exist across the world, few are capable of withstanding natural catastrophes or war—or even something as mundane as a freezer malfunction that could cause irreversible losses.”

Australian chief plant protection officer, Dr Kim Ritman, preparing seed samples for transfer to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway.

Dr Ritman said seeds selected for transfer to the global vault included strains of cotton, chickpea, lentil, sesame, sorghum, wheat, barley, canola, tropical and temperate pasture legumes and grasses and Australian native species that were considered of actual or historical significance to Australia, and didn’t yet feature in the Svalbard collection.

“These varieties have been chosen as they represent Australia’s important history with grain crops and pastures. They are particularly significant given Australia’s proud legacy as a leading producer of world-class crops and pasture based industries,” he said.

The Australian Grains Genebank, which was opened in 2014, has the capacity to hold 200,000 packets of seeds and more than 200 different crop species. In 2017, the collection held about 138,016 different accessions.

The Australian Pastures Genebank, which is managed by the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), has 89,000 accessions of pasture that have been collected from around the world.

“Some are unique. You would never get into those countries again. Australians are quite intrepid in the way they have gone around and collected the material. There is a lot of ‘wild relative’ material, plus Australian natives,” Dr Ritman said.

“The genebanks underpin our agricultural productivity growth because they are stores of unique seeds we can use in breeding and pre-breeding programs to improve the productivity of our agriculture. But is also preserves the seed for future generations.

“So, it benefits society in two ways. One is the immediate agricultural productivity growth and the prosperity of farmers, and the second is for future generations because we don’t know what is coming down the line in an uncertain world.”

HAVE YOUR SAY